|

"Gyil (gourd-resonated xylophone). Dagara people. Falu, Upper West Region, [Ghana] 1990. Rosewood, ebony wood, gourds, spider-egg casings, antelope skin, cord, rubber. Ba Wua, maker. Serves as a funeral xylophone. Displayed with beaters."

So reads the plaque in front of the gyil displayed at the Music Instrument Museum in Phoenix (image on right). It's a short and sweet description that |

just barely touches on the metaphorical surface of the beautiful instrument behind the plaque. [Note: I was introduced to the instrument with the name being pronounced "JHEE-lee" with a soft G and two distinct syllables. The word looks more like -- and a lot of other people I've heard call it -- "JHEE-el" like "eel" with a soft G at the front].

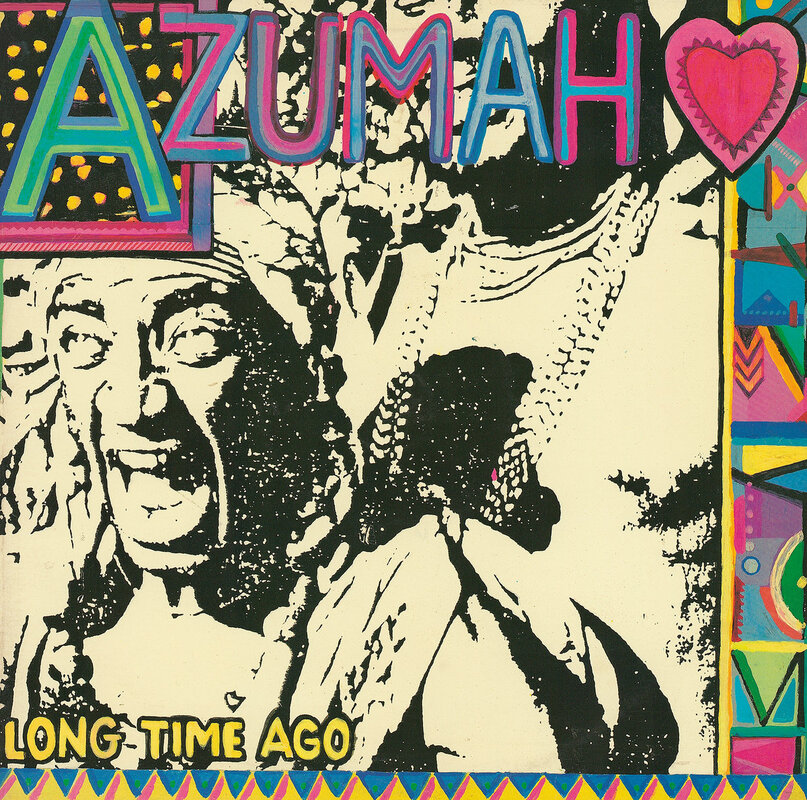

According to the liner notes of Sublime Frequencies DAGARA: Gyil Music of Ghana's Upper West Region, "gyil players remain central to religious and cultural life, playing an indispensable role in funerary rites and festivals and imbuing daily life with music. There are several overlapping gyil traditions in this region that extend over Ghana's border to neighboring Ivory Coast and Burkina Faso and are related to a larger network of xylophone traditions that exist through the Sahel region" (Colter Harper 2020). In the same liner notes, Brian Nowak says that the Dagara demonstrate a deep respect for "the unseen in everyday life. . . . Respecting and honoring the [Kontomble] spirits is a deeply important part of Dagara spirituality. The gyil is the sound of the spirits' song, and a link between the community and the spirit world, a symbol of the sacred in Dagara society" (Nowak 2020).

Nowak adds that "Even for musicians, gyil music provides a deep sense of exploration and is manifested as the spirits' song. The music is said to attract the Kontomble spirits that have provided the knowledge about the instrument and its music. Sacrifices and rituals start at the birth of all new instruments as well as all traditional gyil players who are identified at birth with their thumb tucked between the index and middle finger, born to hold mallets. Becoming a gyil player is a sacred responsibility and a life of self-development and community service by means of the instrument."

I am not a gyil player in any traditional sense. I was not born into it, I have not participated in any rituals to bond me with the instrument, and (it probably goes without saying) I am not Dagara and I am not from Ghana. But I love the living you-know-what out of this instrument and I deeply relate with certain aspects of the philosophy laid out above. Perhaps most importantly, my choice to pursue a career in music was based entirely on what I felt to be a personal obligation for community service. Uncle Ben (Spiderman) says "with great power comes great responsibility," and while my pockets aren't full up with power, I can tell that I'm a lucky person - that I have opportunity - and when I made the decision to make a career out of music, I believed (and still do) that it would be a waste of my opportunity to not use it for some kind of good beyond myself. At the time, I was sure I would be a music teacher. Plans changed. I don't really know where my life will take me, right now, but one thing is for certain - the mission is still a go. Everything I do with music, I do for love. Love of the people I'm performing with and performing for, love of myself (when playing music is therapeutic), and love for music itself.

But what is music? The Dagara say that the music of the gyil is the song of the spirits. Somebody told me something similar once when I was out gigging with my gyil in the early days, and it clicked with a feeling that I had long been able to perceive, but struggled to put into words. Before I can tell you that story, though, I need to go back to the beginning.

According to the liner notes of Sublime Frequencies DAGARA: Gyil Music of Ghana's Upper West Region, "gyil players remain central to religious and cultural life, playing an indispensable role in funerary rites and festivals and imbuing daily life with music. There are several overlapping gyil traditions in this region that extend over Ghana's border to neighboring Ivory Coast and Burkina Faso and are related to a larger network of xylophone traditions that exist through the Sahel region" (Colter Harper 2020). In the same liner notes, Brian Nowak says that the Dagara demonstrate a deep respect for "the unseen in everyday life. . . . Respecting and honoring the [Kontomble] spirits is a deeply important part of Dagara spirituality. The gyil is the sound of the spirits' song, and a link between the community and the spirit world, a symbol of the sacred in Dagara society" (Nowak 2020).

Nowak adds that "Even for musicians, gyil music provides a deep sense of exploration and is manifested as the spirits' song. The music is said to attract the Kontomble spirits that have provided the knowledge about the instrument and its music. Sacrifices and rituals start at the birth of all new instruments as well as all traditional gyil players who are identified at birth with their thumb tucked between the index and middle finger, born to hold mallets. Becoming a gyil player is a sacred responsibility and a life of self-development and community service by means of the instrument."

I am not a gyil player in any traditional sense. I was not born into it, I have not participated in any rituals to bond me with the instrument, and (it probably goes without saying) I am not Dagara and I am not from Ghana. But I love the living you-know-what out of this instrument and I deeply relate with certain aspects of the philosophy laid out above. Perhaps most importantly, my choice to pursue a career in music was based entirely on what I felt to be a personal obligation for community service. Uncle Ben (Spiderman) says "with great power comes great responsibility," and while my pockets aren't full up with power, I can tell that I'm a lucky person - that I have opportunity - and when I made the decision to make a career out of music, I believed (and still do) that it would be a waste of my opportunity to not use it for some kind of good beyond myself. At the time, I was sure I would be a music teacher. Plans changed. I don't really know where my life will take me, right now, but one thing is for certain - the mission is still a go. Everything I do with music, I do for love. Love of the people I'm performing with and performing for, love of myself (when playing music is therapeutic), and love for music itself.

But what is music? The Dagara say that the music of the gyil is the song of the spirits. Somebody told me something similar once when I was out gigging with my gyil in the early days, and it clicked with a feeling that I had long been able to perceive, but struggled to put into words. Before I can tell you that story, though, I need to go back to the beginning.

​I purchased my 2 gyil through the Africa Heartwood Project using a grant from my undergrad, SMU, in the late stages of 2016, in the middle of my senior year. AHP is a 501(c)3 non-profit in the US and registered as an NGO in Ghana. They work in a number of ways to support underserved populations in Ghana, and one of their methods is connecting traditional crafts-makers to broader markets by helping make their products available on the internet - including major marketplaces like Amazon. Yes, I bought my gyil on Amazon.

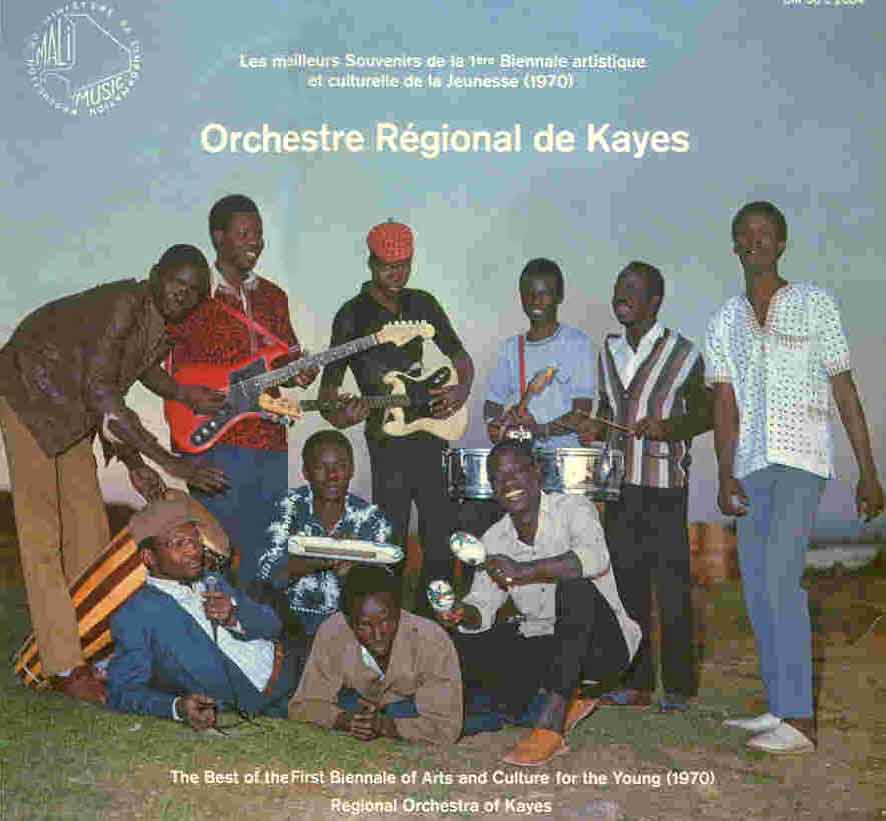

My relationship with the gyil started on awkward footing because I had originally wanted to get a couple of balafon (from Mali, part of the "larger network of xylophone traditions" in the region that were mentioned by Harper). You see, the director of the World Music Ensemble at SMU, Jamal Mohamed, had a pair of balafon that I had the opportunity to play on occasion throughout my undergrad, and I so thoroughly enjoyed the music I was able to create with them that I needed to get my own so that I could take them home for practice and use them for gigs. AHP had a balafon available, but the rub was this: Jamal's balafon were laid out in a pentatonic major scale (1,2,3,_,5,6_,1--or "the black keys {starting on F#}") and that's why improvising with them was so intuitive. The rindik, a bamboo xylophone that I had learned to play in Bali, is also typically laid out in something that is near to a pentatonic major scale (the rigid idea of pitch that we have in European-American music does not exist in Bali {and a lot of other places for that matter} where neighboring towns or villages can have sets of instruments with their own unique tuning; the pentatonic major scale is near enough to certain tunings that you could play an approximation of a Balinese rindik song on a European-American instrument using that scale). The balafon sold by AHP was in a heptatonic major scale, so it would be a completely different playing style than what I had become used to. However, they also sold gyil that happened to be in the pentatonic major tuning with which I was familiar. The rest, is ... well, I mean keep reading because I'm about to tell you the rest.

Two gyil arrived in giant boxes on my front doorstep. They took up the entire entryway to my small apartment and, because of the size of the instruments, each one was actually contained in two separate boxes with the open ends facing each other and taped over each other to create one single mega-box. AHP had gone out of their way to send me a pair of gyil that were pretty well pitch-matched, and they ended up being almost perfect. The slight dissonance between each pairing of notes across the two gyil creates a sort of chorus effect that reminded me of the Balinese tradition of de-tuning one instrument in a pair to create a beat frequency (I've been told the ideal is a 7 Hz difference). It's a natural shimmer or vibrato built into the instruments through physics.

Right off the bat, I started jamming. Probably my first original record (unpublished) was "Gyli Rock" [sic], the SoundCloud track embedded at the top of this post that I recorded in my bedroom on GarageBand using my guitar, some shakers, and the two gyil. In that recording, I played one melodic line simultaneously on both gyil, with a mic hanging over the middle of them. The same chord progression eventually became "The Fox and the Lion," the headliner from my first album "The Front of the Line." But before that, I had to go through heartbreak.

Ever since I read Part I of Don Quixote in high school, I've been a hopeless romantic (Hamlet didn't help, either). When My first girlfriend and I separated shortly before Christmas 2016, it was incredibly difficult for me. I came out on the other side of it with a heart full of pain that needed to be expressed, and I found a way to express it through music in general and through the gyil in particular. A few months later (the date was March 3, 2017), I was still on the path to recovery. I had a lot of doubt about choices I had made for my career and my personal life - "being a musician is childish." "world music? you can't make a living doing that." "you need to grow up and do something that's actually productive and meaningful. not just something fun." But then something happened that brought me back into myself as if I had been zapped with jumper cables.

My relationship with the gyil started on awkward footing because I had originally wanted to get a couple of balafon (from Mali, part of the "larger network of xylophone traditions" in the region that were mentioned by Harper). You see, the director of the World Music Ensemble at SMU, Jamal Mohamed, had a pair of balafon that I had the opportunity to play on occasion throughout my undergrad, and I so thoroughly enjoyed the music I was able to create with them that I needed to get my own so that I could take them home for practice and use them for gigs. AHP had a balafon available, but the rub was this: Jamal's balafon were laid out in a pentatonic major scale (1,2,3,_,5,6_,1--or "the black keys {starting on F#}") and that's why improvising with them was so intuitive. The rindik, a bamboo xylophone that I had learned to play in Bali, is also typically laid out in something that is near to a pentatonic major scale (the rigid idea of pitch that we have in European-American music does not exist in Bali {and a lot of other places for that matter} where neighboring towns or villages can have sets of instruments with their own unique tuning; the pentatonic major scale is near enough to certain tunings that you could play an approximation of a Balinese rindik song on a European-American instrument using that scale). The balafon sold by AHP was in a heptatonic major scale, so it would be a completely different playing style than what I had become used to. However, they also sold gyil that happened to be in the pentatonic major tuning with which I was familiar. The rest, is ... well, I mean keep reading because I'm about to tell you the rest.

Two gyil arrived in giant boxes on my front doorstep. They took up the entire entryway to my small apartment and, because of the size of the instruments, each one was actually contained in two separate boxes with the open ends facing each other and taped over each other to create one single mega-box. AHP had gone out of their way to send me a pair of gyil that were pretty well pitch-matched, and they ended up being almost perfect. The slight dissonance between each pairing of notes across the two gyil creates a sort of chorus effect that reminded me of the Balinese tradition of de-tuning one instrument in a pair to create a beat frequency (I've been told the ideal is a 7 Hz difference). It's a natural shimmer or vibrato built into the instruments through physics.

Right off the bat, I started jamming. Probably my first original record (unpublished) was "Gyli Rock" [sic], the SoundCloud track embedded at the top of this post that I recorded in my bedroom on GarageBand using my guitar, some shakers, and the two gyil. In that recording, I played one melodic line simultaneously on both gyil, with a mic hanging over the middle of them. The same chord progression eventually became "The Fox and the Lion," the headliner from my first album "The Front of the Line." But before that, I had to go through heartbreak.

Ever since I read Part I of Don Quixote in high school, I've been a hopeless romantic (Hamlet didn't help, either). When My first girlfriend and I separated shortly before Christmas 2016, it was incredibly difficult for me. I came out on the other side of it with a heart full of pain that needed to be expressed, and I found a way to express it through music in general and through the gyil in particular. A few months later (the date was March 3, 2017), I was still on the path to recovery. I had a lot of doubt about choices I had made for my career and my personal life - "being a musician is childish." "world music? you can't make a living doing that." "you need to grow up and do something that's actually productive and meaningful. not just something fun." But then something happened that brought me back into myself as if I had been zapped with jumper cables.

March 3 was "Have Donuts and Coffee with a Cop" day in the Dallas area. I was playing a solo gig with one of my gyil for Music on Mockingbird (the weekly outdoor concert series I established with Bridge the Gap Chamber Players). I took a moment's break to get coffee from the food truck that was just across the way while the host from Mockingbird Station watched the gyil. When I returned, somebody was playing it. It just so happens that one of the transit officers (Mockingbird Station is a major stop for the DART urban train in Dallas) had grown up in Ghana and was taught to play gyil in school as a kid (pictures above). He showed us a couple of tunes and went back to his patrol.

Then, just when I thought the day couldn't get more crazy-cool, another dude showed up. I couldn't see him all that well because he approached from the direction of the sun. He walked right up to the gyil, told me he liked my playing, and asked if he could try. I handed him the mallets and he played for about a minute while singing something that could have been flamenco style or something else. It was visceral and improvised and fluttering. It was beautiful. He handed the mallets back, thanked me, and left me with this nugget of wisdom that has shaped my life ever since. "Music is God here on Earth."

​That was the moment that I told you about at the beginning of this post. In that moment I felt like God had seen me in my emotional turmoil and set me up to run into this guy and hear exactly what I needed to hear to snap my head out of the doldrums where I had been aimlessly rocking to-&-fro for the past few months. I knew in that moment that I was on the right track - whatever that track was. Music was where I belonged. Bringing music from other parts of the world into the spotlight for people in my community to open their hearts and minds to other people and other perspectives (my primary goal as an ethnomusicologist and "world music" performer) was what I needed to be doing. And there I was, doing it.

Then, just when I thought the day couldn't get more crazy-cool, another dude showed up. I couldn't see him all that well because he approached from the direction of the sun. He walked right up to the gyil, told me he liked my playing, and asked if he could try. I handed him the mallets and he played for about a minute while singing something that could have been flamenco style or something else. It was visceral and improvised and fluttering. It was beautiful. He handed the mallets back, thanked me, and left me with this nugget of wisdom that has shaped my life ever since. "Music is God here on Earth."

​That was the moment that I told you about at the beginning of this post. In that moment I felt like God had seen me in my emotional turmoil and set me up to run into this guy and hear exactly what I needed to hear to snap my head out of the doldrums where I had been aimlessly rocking to-&-fro for the past few months. I knew in that moment that I was on the right track - whatever that track was. Music was where I belonged. Bringing music from other parts of the world into the spotlight for people in my community to open their hearts and minds to other people and other perspectives (my primary goal as an ethnomusicologist and "world music" performer) was what I needed to be doing. And there I was, doing it.

|

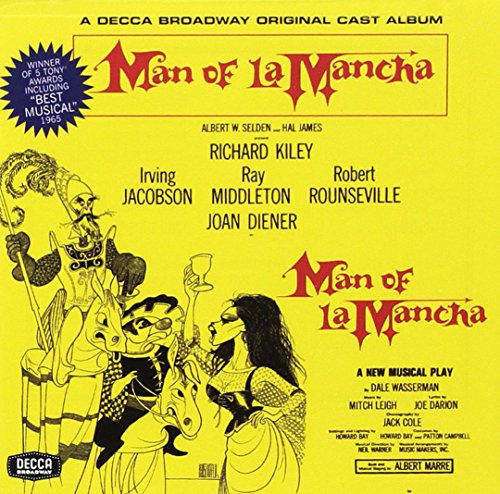

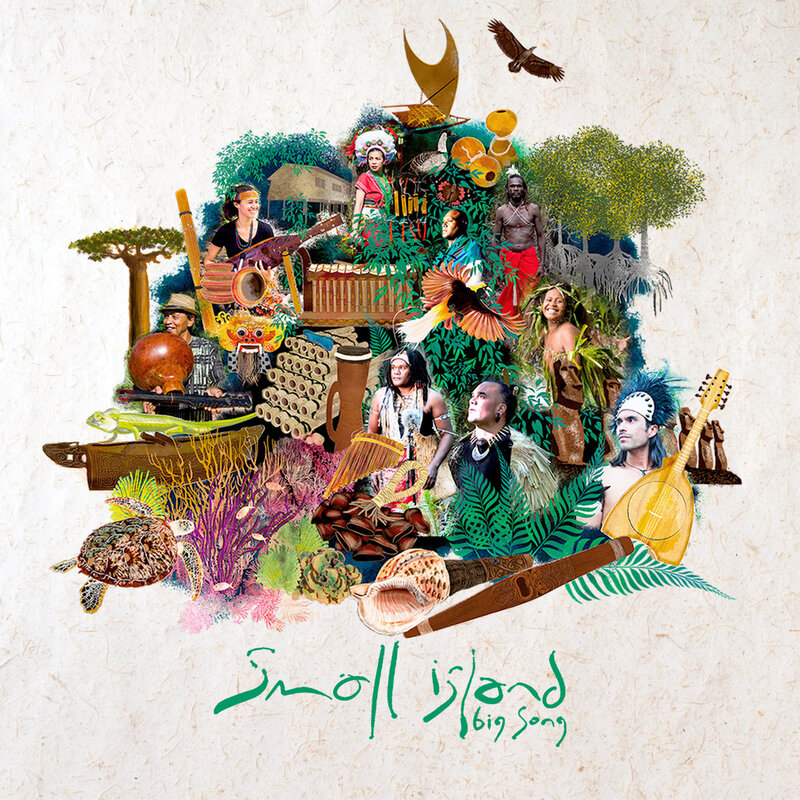

That was the same semester that I would be graduating from SMU and, as a consequence, it was the semester of my senior recital. I knew I would be remiss not to perform something from the infinite repertoire that is "world music" since that was my real passion, and the universe aligned in just the right way to help me along once again. One of my professors, during a marimba masterclass, played a piece arranged by an artist called Valerie Naranjo. The piece was a traditional gyil song (from the Lobi, rather than the Dagara) that had been transcribed and arranged for marimba.​

|

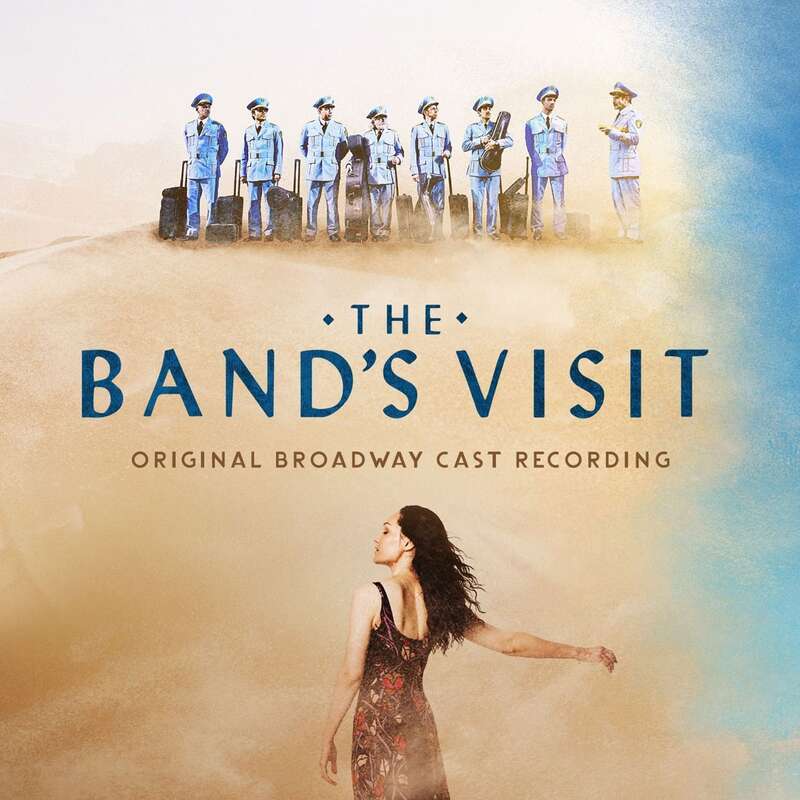

Valerie, it turns out, is a superstar. She has been in the SNL band for a number of years and played in the pit for the Broadway version of The Lion King. She is also a key reason that women in Ghana are allowed to play the gyil now. Valerie, from Southern Colorado, studied the gyil here in the US as well as in Ghana, and became such a virtuosic performer that "her playing of the gyil's traditional repertoire in Ghana's Kobine Festival of Traditional Music [1988] led to the declaration of a chiefly decree in the Dagara nation that women be allowed to play the instrument for the first time" (from her bio on the NYU website).

I connected with Valerie and, with her input, transposed "Nite Song" back to gyil for my senior recital (I say transposed because I never wrote anything down - I simply read off the full-staff marimba arrangement and mentally converted what was on the page to fit the instrument I had in front of me). Here's a link to my performance of "Nite Song" on YouTube (image above is from this performance).

I connected with Valerie and, with her input, transposed "Nite Song" back to gyil for my senior recital (I say transposed because I never wrote anything down - I simply read off the full-staff marimba arrangement and mentally converted what was on the page to fit the instrument I had in front of me). Here's a link to my performance of "Nite Song" on YouTube (image above is from this performance).

Since then, I've performed frequently on the gyil. With some of my best friends, Brandon Carson, Sam Park (in the wide image earlier in this post), Austin Allen, and others for improvised duets, and sometimes solo (including my solo debut at the Meyerson Symphony Center in Dallas in 2018 - see the instagram post below).

|

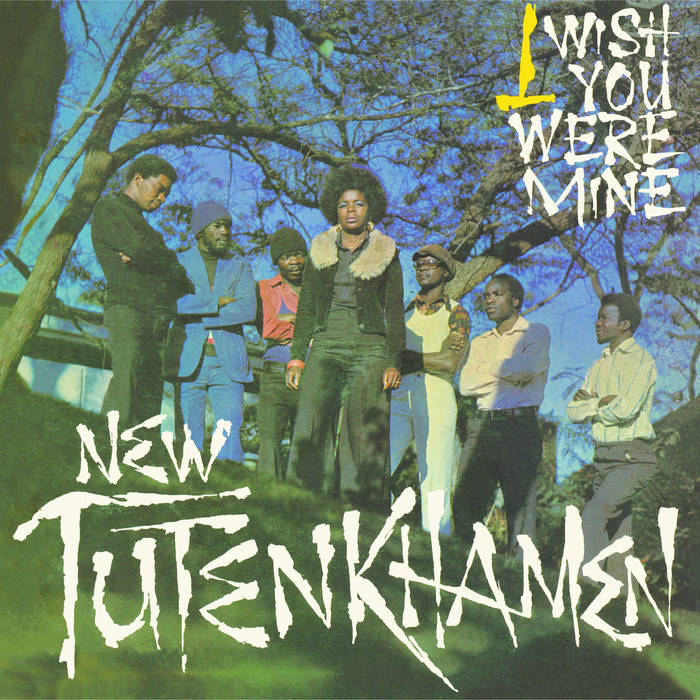

Some gigs were paid, others were not. Early during the COVID Summer, Sam Park and I walked from my house out to the dead, empty streets of Lower Lower Greenville and set up my gyil and played for hours to help the silence in its mourning. I've also included the gyil in ethnomusicology master-classes that I've presented to middle- and high-schoolers. I've developed several arrangements of some of my favorite songs for gyil, including the astonishing "A Man / Me / Then Gyil" (an adaptation of Rilo Kiley's "A Man / Me/ Then Jim").

But this post isn't about all the things I've done with the gyil. It's about what the gyil has done for me. ​Like I said before - I'm not a traditional gyil player in any sense. The music I play isn't Dagara or Lobi, and I haven't gone through any initiations. In fact, I've never learned anything about playing gyil directly from another person who knew something about it. What I do with the instrument is entirely self-taught or simply made up. But it's not a problem for me that I'm not doing anything traditional. when I play the gyil, the music flows directly from my heart, through my hands, and into and then out of the instrument, without any self-critical filter breaking up the sequence. |

When I'm hurting, I can play the gyil to help heal. When I'm joyful, playing the gyil helps me celebrate. It would be a mistake to think that an instrument that is easier to play is "less" "sophisticated" than anything else. The gyil is an incredible piece of technology. The resonating frequency of each gourd is matched with that of the bar it hangs under to amplify the sound pitch. Spider egg casings (or, as on mine, paper) cover small holes in the gourd resonators to add a buzzing sound effect (see my lecture on altuceciance and latuceciance with the Cuyamungue Institutehere). And complex musical-theoretical traditions govern the music that is played on the instruments in traditional contexts. The fact that the gyil is so versatile and so adaptable is the icing on the cake. It's the reason the gyil has overtaken so much of my heart that when I drove home to Dallas for s couple of months in the summer between my two years of grad school with a car full of textbooks and clothes that I absolutely had to make space for one of my gyil. I would not be going "home" without it.

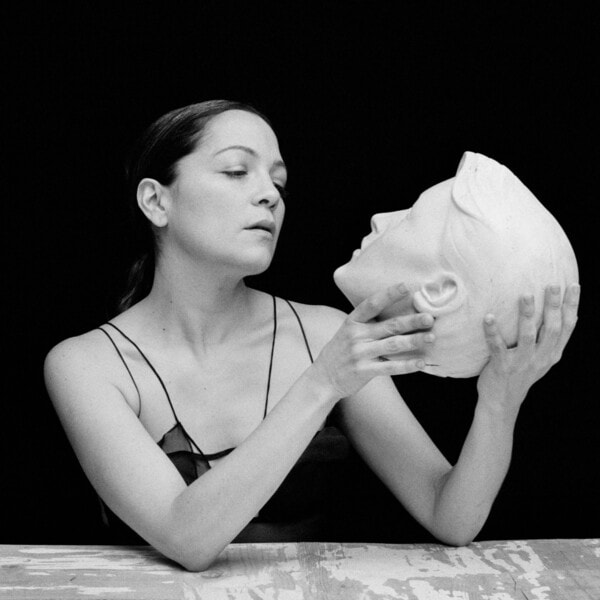

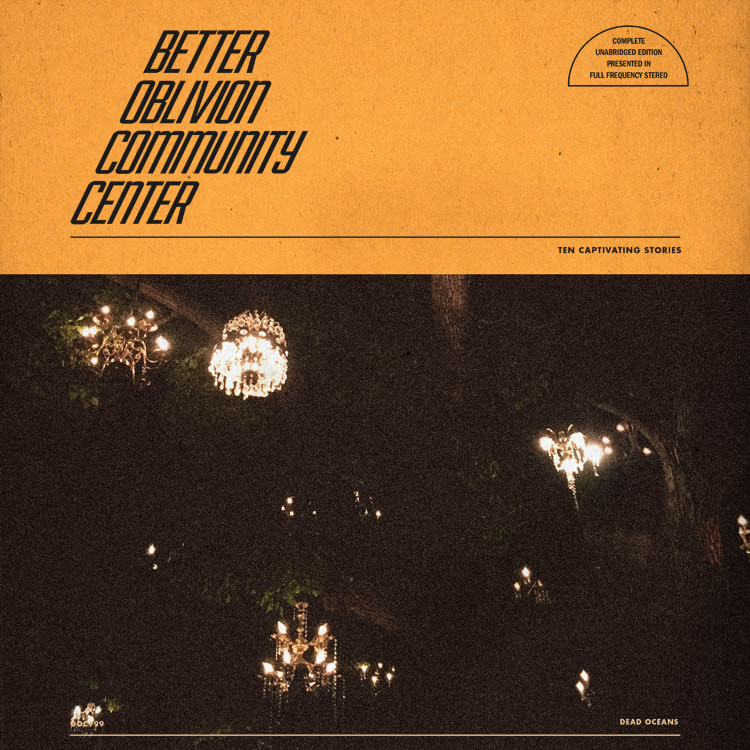

When you look at me, you shouldn't see a gyil player. You should see someone who is played by the gyil. After loving my gyil and they sounds they make for so long, it was my honor to feature them on the record that is the culmination of my time at ASU. My latest single "Here & Everywhere," is made up of some of my favorite sounds and instruments, but right in the middle (well, actually slightly panned to the left and right) are my gyil, carrying on the rambunctious jam melody during the bridge sections and commenting on the other instrumental lines throughout. The album cover shows myself and one of my gyil, and though it may seem to be the other way around, the instrument in this picture is in fact holding me up, as both my gyil have done now for more than half a decade.

I hope that you will go listen to more gyil music, traditional and otherwise, and that you enjoy "Here & Everywhere."

Lawson Malnory

Phoenix, AZ

​11 April 2022

When you look at me, you shouldn't see a gyil player. You should see someone who is played by the gyil. After loving my gyil and they sounds they make for so long, it was my honor to feature them on the record that is the culmination of my time at ASU. My latest single "Here & Everywhere," is made up of some of my favorite sounds and instruments, but right in the middle (well, actually slightly panned to the left and right) are my gyil, carrying on the rambunctious jam melody during the bridge sections and commenting on the other instrumental lines throughout. The album cover shows myself and one of my gyil, and though it may seem to be the other way around, the instrument in this picture is in fact holding me up, as both my gyil have done now for more than half a decade.

I hope that you will go listen to more gyil music, traditional and otherwise, and that you enjoy "Here & Everywhere."

Lawson Malnory

Phoenix, AZ

​11 April 2022