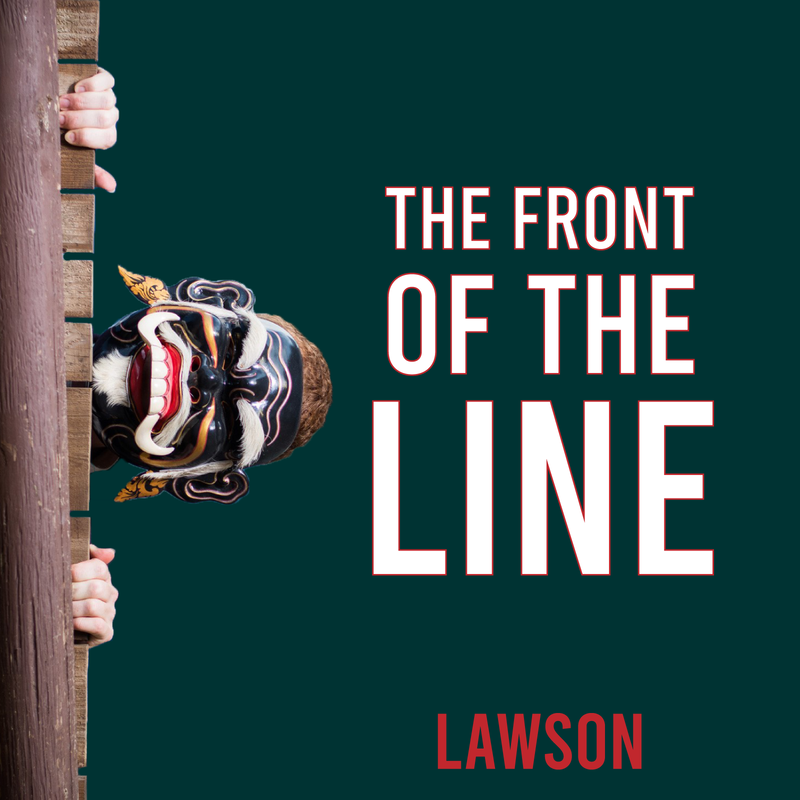

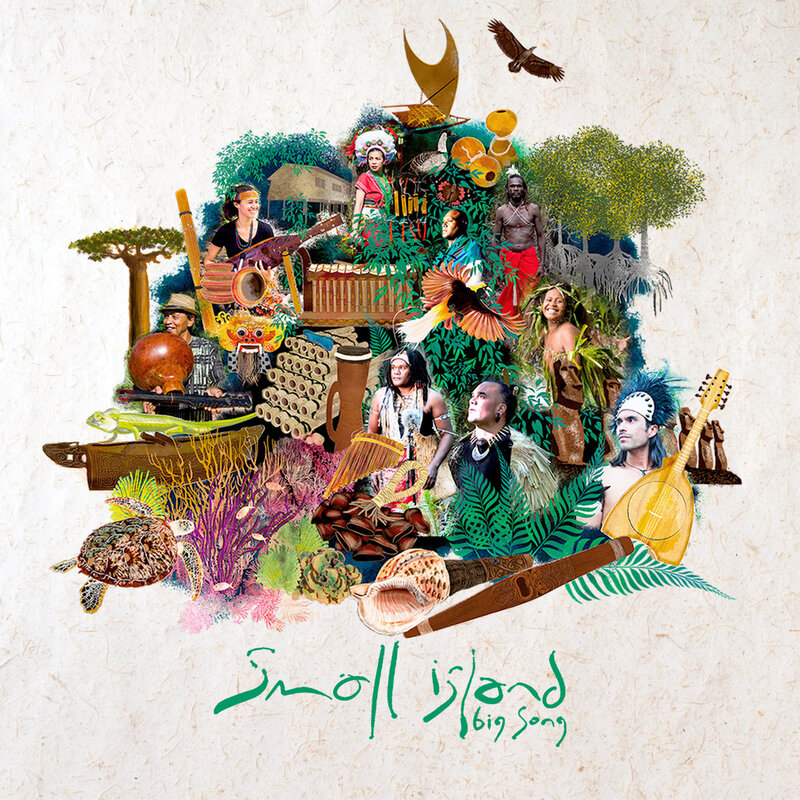

| My first album, titled "The Front of the Line," features a lot of stuff that I had to leave the United States to learn about. I know that as a male, non-Hispanic caucasian-American, I am in a prime position to be accused of culturally appropriating the traditions of the people who have inspired me and my art. The Anti-Oppression Resource and Training Alliance has a useful page describing Cultural Misappropriation here. In this blog post, I will do my best to accurately summarize the original meaning and/or usage (as I understand them) of the various elements I have invited into my own personal culture for this album. Unfortunately, I can never capture the essence of the cultures, traditions, and people who I describe with mere words, so I encourage you to do additional research on your own and visit the places where these beautiful instruments, masks, clothes, and people come from. It will give you a deeper and more | Me and Nate, my first time in Bali (2014) |

fulfilling experience in art and life. To be clear, no one has accused me of cultural misappropriation. I just wanted to get in front of it and take the opportunity to share more information about the cultures I have done my best to not appropriate.

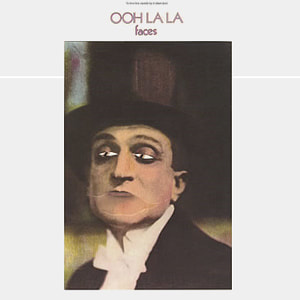

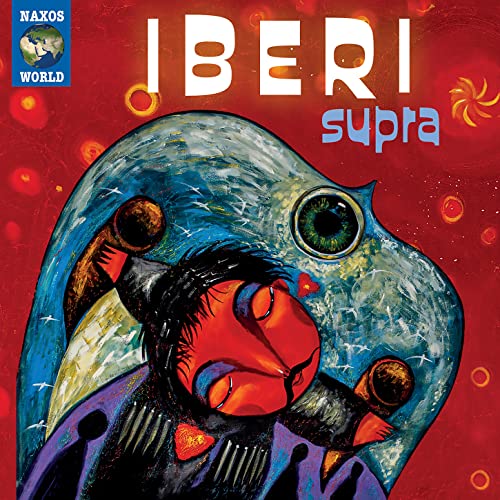

The first cultural element that you will probably notice is the mask featured in the album artwork. This mask is from the Indonesian island of Bali. I purchased it from a master craftsman there in the Summer of 2018. Bali has an incredibly intricate tradition of masked dance that is intimately connected to its equally intricate musical traditions. There are two "characters" who are represented by masks of this appearance and they are difficult to differentiate. However, my research allows me to confidently say that this mask is that of Jero Gede (the other option is Sida Karya Selem, who never seems to be portrayed with ears). Jero Gede is part of the Barong tradition, and is frequently featured as part of Barong Landung processions, wherein giant puppets (often Jero Gede and its companion Jero Luh) "patrol the village borders, repelling the low spirits and driving them back to their homes" (Judy Slattum & Paul Schraub, Balinese Masks: Spirits of an Ancient Drama). "Jero Gede loooks like a grotesque, black-faced monster but is actually a harmless clown. His appearance is based on that of a legendary incestuous demon from whom he inherited his curved tusks. His deep-set eyes, low forehead, and bushy white eyebrows give him a simian look, whereas the well-proportioned rounded nose and cheeks suggest that he has a jolly disposition. His large buck teeth, set off by blood red lips, demonstrate his power. The darkness of his mask, body hair, and costume symbolize his Indian ancestry and also our subconscious instincts, passions, and desires. The graying, shaggy hair and beard indicate that Jero Gede is actually an older man. His ears are adorned with decorations called tindik, a form of ancient jewelry from Hindu Java worn by men. His fangs give him the untamed, unbridled nature of one driven to pursue needs that are often sought but never satiated" (Slattum & Schraub). I featured this mask on the cover of the album (and in one of the music videos) because it is beautiful and because, like Jero Gede, I want my music to scare away the "low spirits" that manifest for me as sadness, anger, &c, and to replace them with joy. Moreover, the completion of this album was itself a desire that was "sought after but never satiated" for many years, and I believe it is fitting that Jero Gede and I both get a little of the satisfaction that the Rolling Stones never could.

In the recording process, I used many instruments that were developed outside of the European music tradition. I will go ahead and list all the instruments I played (in order of appearance) on the album here and add notes when relevant.

Acoustic Guitar - I used an acoustic guitar by Seagull, handmade in the village of Princeville, Quebec. (Tracks 1, 2, 6)

Drumset - I used two different drumsets in this recording process. I don't know where either was made but I really doubt I'm going to catch flack for that. (Tracks 2, 4)

Maracas - Shakers and rattles of all different shapes and sizes are used the world over. Maracas specifically describe a style frequently featured in Caribbean and South American music. They are likely derivative (or identical descendants) of shakers used by the indigenous peoples of these areas since before the noted arrival of Europeans at the end of the 15th Century. Maracas crossed-over into popular music decades ago. I believe mine were made in Mexico, and that I acquired them in San Antonio. (Track 2)

Guiro - Scrapers are also used all over the world. "Guiro" denotes a Caribbean instrument frequently used in the music of Cuba, Puerto Rica, Mexico, and many other places. The guiro also crossed-over into popular music quite a ways back. Oddly enough, the guiro used on this album was actually crafted in Bali, and purchased from a music shop in Ubud in the Summer of 2019. (Track 2)

Electric Guitar - My electric guitar (a very American tradition) is an Epiphone Les Paul model. The same axe was also used in the recording of the first EP of The Happy Alright and several of their performances. Epiphone was founded in Smyrna, at the time part of the Ottoman Empire, in 1873. They are currently based in Nashville and manufacture most of their instruments in China. (Track 2, 3, 4)

Congas - Traditionally known as Tumbadoras, congas are a Cuban drum, the design of which is most likely based on African drums that were replicated from memory by people taken as slaves and their descendants. Congas are a crucial part of many different styles of music, from folkloric Cuban traditions to Salsa, Jazz, and Pop. I learned a small amount about congas and the related traditions when I visited Matanzas, Cuba, in 2019. I have much still to learn, but I love the sound the create and the rhythms associated with them. My congas are by Tycoon, out of Thailand. (Tracks 3, 6)

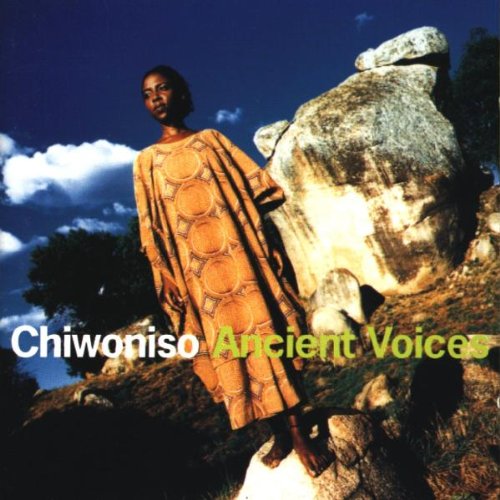

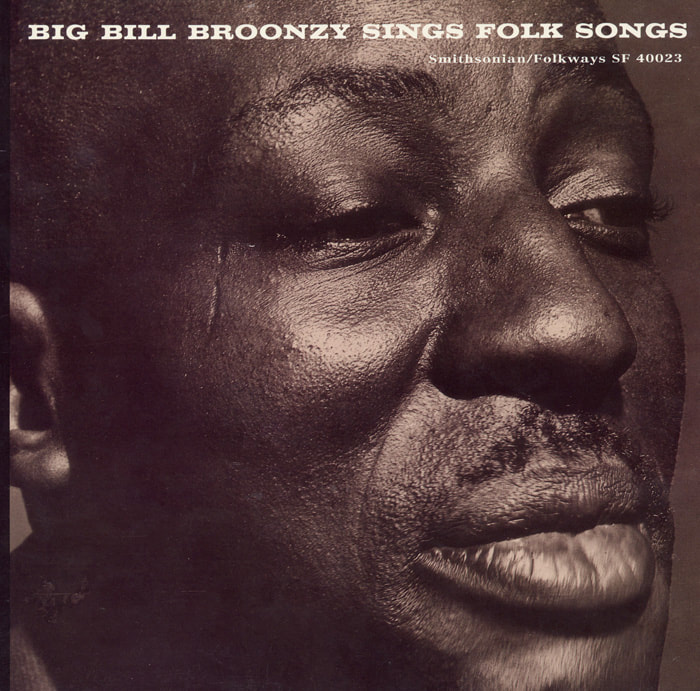

Mbira - My favorite instrument of every one I've ever heard, the mbira is what we commonly refer to as a "thumb piano." There are actually hundreds of kinds of mbira (or sanza, kalimba, &c.) from all over Southern Africa. The type I used is called the Mbira Dzavadzimu ("Great mbira of the ancestors" is one translation) of the Shona people, who reside mostly in Zimbabwe. One traditional usage of the instrument is to provide music at ceremonies where people convene to communicate with spirits of deceased ancestors. There is a vast repertoire of mbira music, and performances involve much improvisation. The music I play on the album with the mbira is actually the traditional Shona song Nhemamusasa, which can mean "Cutting branches for a temporary shelter." This is probably the most frequently-recorded traditional Shona piece (especially by non-Africans). When I play the mbira, I feel a spiritual connection of my own, though whether it is with my ancestors, with God, or with some unnamed power, I know not. I wanted to share my love for the instrument and its music and my appreciation for the people who brought it into the world by including my own twist on Nhemamusasa on my album. If you listen to the words on the track, you may find that "Cutting Branches for a Temporary Shelter" is an apt metaphor. My usage of two mbira, playing generally the same rhythm while temporally offset, combined with rhythmic clapping, a shaker, and singing, pretty accurately reproduces a traditional performance. I purchased my instrument from the non-profit Mbira.org, which provides fair compensation to Zimbabweans musicians who are expert instrument-makers. Mine was crafted by Samson Bvure. (Track 5)

Shekere - The Shekere is another African shaker-type instrument made from a large gourd with beads around the outside. Variants of the instrument are used all over Africa and in the African diaspora. I was introduced to the instrument by the reputed world music icon Jamal Mohamed, and acquired my shekere in McKinney, Texas, from an African Art collector. (Track 5)

Birds - (This one's for PETA) No birds were harmed in the recording of this album. The birds featured are native to Texas and were recorded in my backyard. (Track 6)

Clave - The clave is another Cuban instrument, fundamental to the Salsas and Rumbas all our parents talk about, and equally important, if not more so, in much folkloric music. They play a repetitive rhythm upon which the patterns of the melody and all other instruments are layered. There are many different specific clave rhythms that can be used, and I used one called Yambu in the 6th track on the album. The conga parts on that track are also part of the Yambu family, but I altered the relative tempo of certain parts to better fit with the melody of the song. Claves, and Cuban rhythms, have been inspiring Popular music in the United States since the latter half of the 19th Century. For more on that topic, I recommend Ned Sublette's "Cuba and Its Music." It's a heck of a book. The claves I used on The Front of the Line are by the company LP (Latin Percussion), and of unknown geographic origin. (Track 6)

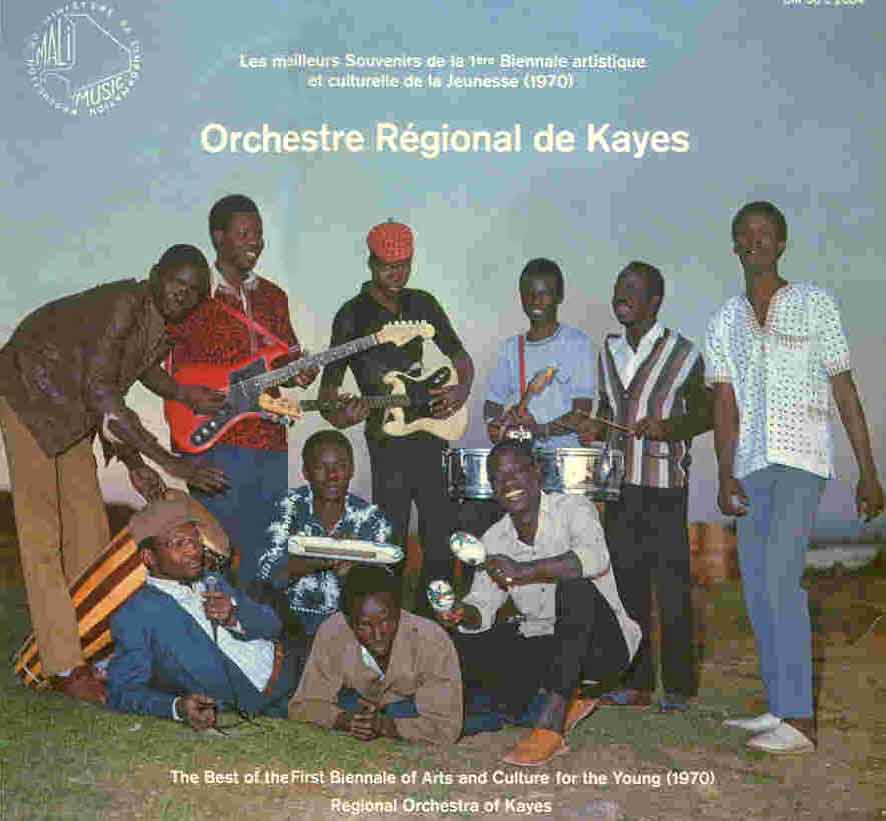

Gyil - The gyil is a xylophone used my several people-groups from West-Africa, especially Ghana. It consists of keys carved from local hardwood, resonators made from calabash gourds, a wooden frame, and ropes to hold it all together. I encountered the balafon, a similar instrument from Mali, north of Ghana, while studying with Jamal Mohamed. I was turned onto the gyil when preparing my senior recital at SMU. I corresponded with noted gyil performer Valerie Naranjo to learn about the instrument and in preparation for performance of "Nite Song," one of her marimba arrangements of traditional gyil music (I mentally arranged it back to gyil for my recital). My gyil (I have a pair) were purchased through the African Heartwood Project, which is a fair-trade organization helping artisans in Africa sell their work via the internet. (Track 6)

Ukulele - The ukulele is generally accepted to be the Hawaiian adaptation of a Portuguese instrument called "machete." It has been featured in pop music for many years, but was given legendary status through the music of Israel Kamakawiwo'ole (AKA "Iz"). He is the guy that improvised that "Over the Rainbow" we all cry when we hear. I love the music of Iz and I love the sound of the ukulele. It, like the cowboy's acoustic guitar, is an instrument made to sing with. The final track on the album features only my ukulele and my voice, and it was the instrument that inspired that particular song - I simply followed where it led. My ukulele was made by the Kala brand. (Track 7)

In some of my promotional materials I featured sarongs and saputs from Bali. These are traditional clothes used in ceremonies and in daily life by men and women (I think the saput might just be for guys). All of my sarongs and saputs are from Bali, purchased from local artisans or merchants. I have worn them to many Meadows World Music Ensemble (SMU) performances for their beauty and because they're actually really comfortable. I also used a Bondres mask in a music video. This is another type of Balinese mask that I purchased from its carver while in Bali. For more on Bondres masks, check out this page.

In summary, I am very much aware that cultural misappropriation is a bad thing. It involves taking advantage of people from less well-to-do cultures by using their arts and their creativity to turn a profit without providing any benefit to the original artists. I have done my very best to avoid this, and I believe I have been successful. I study the instruments and styles that I bring into my music and I am deeply passionate about building a global community of unique cultures joined together through compassion and understanding. None of the music on my album is "authentic," but rather the song styles are fusions of sounds, rhythms, and ideas from all over the world. This follows a tradition of artistic synthesis that goes back centuries, if not millenia, to the first time somebody met somebody else from out-of-town who had a cool new idea.

I hope you enjoy the album and are inspired to learn more about the people and cultures that inspired me!

Lawson

16 May 2020

Dallas, TX

The first cultural element that you will probably notice is the mask featured in the album artwork. This mask is from the Indonesian island of Bali. I purchased it from a master craftsman there in the Summer of 2018. Bali has an incredibly intricate tradition of masked dance that is intimately connected to its equally intricate musical traditions. There are two "characters" who are represented by masks of this appearance and they are difficult to differentiate. However, my research allows me to confidently say that this mask is that of Jero Gede (the other option is Sida Karya Selem, who never seems to be portrayed with ears). Jero Gede is part of the Barong tradition, and is frequently featured as part of Barong Landung processions, wherein giant puppets (often Jero Gede and its companion Jero Luh) "patrol the village borders, repelling the low spirits and driving them back to their homes" (Judy Slattum & Paul Schraub, Balinese Masks: Spirits of an Ancient Drama). "Jero Gede loooks like a grotesque, black-faced monster but is actually a harmless clown. His appearance is based on that of a legendary incestuous demon from whom he inherited his curved tusks. His deep-set eyes, low forehead, and bushy white eyebrows give him a simian look, whereas the well-proportioned rounded nose and cheeks suggest that he has a jolly disposition. His large buck teeth, set off by blood red lips, demonstrate his power. The darkness of his mask, body hair, and costume symbolize his Indian ancestry and also our subconscious instincts, passions, and desires. The graying, shaggy hair and beard indicate that Jero Gede is actually an older man. His ears are adorned with decorations called tindik, a form of ancient jewelry from Hindu Java worn by men. His fangs give him the untamed, unbridled nature of one driven to pursue needs that are often sought but never satiated" (Slattum & Schraub). I featured this mask on the cover of the album (and in one of the music videos) because it is beautiful and because, like Jero Gede, I want my music to scare away the "low spirits" that manifest for me as sadness, anger, &c, and to replace them with joy. Moreover, the completion of this album was itself a desire that was "sought after but never satiated" for many years, and I believe it is fitting that Jero Gede and I both get a little of the satisfaction that the Rolling Stones never could.

In the recording process, I used many instruments that were developed outside of the European music tradition. I will go ahead and list all the instruments I played (in order of appearance) on the album here and add notes when relevant.

Acoustic Guitar - I used an acoustic guitar by Seagull, handmade in the village of Princeville, Quebec. (Tracks 1, 2, 6)

Drumset - I used two different drumsets in this recording process. I don't know where either was made but I really doubt I'm going to catch flack for that. (Tracks 2, 4)

Maracas - Shakers and rattles of all different shapes and sizes are used the world over. Maracas specifically describe a style frequently featured in Caribbean and South American music. They are likely derivative (or identical descendants) of shakers used by the indigenous peoples of these areas since before the noted arrival of Europeans at the end of the 15th Century. Maracas crossed-over into popular music decades ago. I believe mine were made in Mexico, and that I acquired them in San Antonio. (Track 2)

Guiro - Scrapers are also used all over the world. "Guiro" denotes a Caribbean instrument frequently used in the music of Cuba, Puerto Rica, Mexico, and many other places. The guiro also crossed-over into popular music quite a ways back. Oddly enough, the guiro used on this album was actually crafted in Bali, and purchased from a music shop in Ubud in the Summer of 2019. (Track 2)

Electric Guitar - My electric guitar (a very American tradition) is an Epiphone Les Paul model. The same axe was also used in the recording of the first EP of The Happy Alright and several of their performances. Epiphone was founded in Smyrna, at the time part of the Ottoman Empire, in 1873. They are currently based in Nashville and manufacture most of their instruments in China. (Track 2, 3, 4)

Congas - Traditionally known as Tumbadoras, congas are a Cuban drum, the design of which is most likely based on African drums that were replicated from memory by people taken as slaves and their descendants. Congas are a crucial part of many different styles of music, from folkloric Cuban traditions to Salsa, Jazz, and Pop. I learned a small amount about congas and the related traditions when I visited Matanzas, Cuba, in 2019. I have much still to learn, but I love the sound the create and the rhythms associated with them. My congas are by Tycoon, out of Thailand. (Tracks 3, 6)

Mbira - My favorite instrument of every one I've ever heard, the mbira is what we commonly refer to as a "thumb piano." There are actually hundreds of kinds of mbira (or sanza, kalimba, &c.) from all over Southern Africa. The type I used is called the Mbira Dzavadzimu ("Great mbira of the ancestors" is one translation) of the Shona people, who reside mostly in Zimbabwe. One traditional usage of the instrument is to provide music at ceremonies where people convene to communicate with spirits of deceased ancestors. There is a vast repertoire of mbira music, and performances involve much improvisation. The music I play on the album with the mbira is actually the traditional Shona song Nhemamusasa, which can mean "Cutting branches for a temporary shelter." This is probably the most frequently-recorded traditional Shona piece (especially by non-Africans). When I play the mbira, I feel a spiritual connection of my own, though whether it is with my ancestors, with God, or with some unnamed power, I know not. I wanted to share my love for the instrument and its music and my appreciation for the people who brought it into the world by including my own twist on Nhemamusasa on my album. If you listen to the words on the track, you may find that "Cutting Branches for a Temporary Shelter" is an apt metaphor. My usage of two mbira, playing generally the same rhythm while temporally offset, combined with rhythmic clapping, a shaker, and singing, pretty accurately reproduces a traditional performance. I purchased my instrument from the non-profit Mbira.org, which provides fair compensation to Zimbabweans musicians who are expert instrument-makers. Mine was crafted by Samson Bvure. (Track 5)

Shekere - The Shekere is another African shaker-type instrument made from a large gourd with beads around the outside. Variants of the instrument are used all over Africa and in the African diaspora. I was introduced to the instrument by the reputed world music icon Jamal Mohamed, and acquired my shekere in McKinney, Texas, from an African Art collector. (Track 5)

Birds - (This one's for PETA) No birds were harmed in the recording of this album. The birds featured are native to Texas and were recorded in my backyard. (Track 6)

Clave - The clave is another Cuban instrument, fundamental to the Salsas and Rumbas all our parents talk about, and equally important, if not more so, in much folkloric music. They play a repetitive rhythm upon which the patterns of the melody and all other instruments are layered. There are many different specific clave rhythms that can be used, and I used one called Yambu in the 6th track on the album. The conga parts on that track are also part of the Yambu family, but I altered the relative tempo of certain parts to better fit with the melody of the song. Claves, and Cuban rhythms, have been inspiring Popular music in the United States since the latter half of the 19th Century. For more on that topic, I recommend Ned Sublette's "Cuba and Its Music." It's a heck of a book. The claves I used on The Front of the Line are by the company LP (Latin Percussion), and of unknown geographic origin. (Track 6)

Gyil - The gyil is a xylophone used my several people-groups from West-Africa, especially Ghana. It consists of keys carved from local hardwood, resonators made from calabash gourds, a wooden frame, and ropes to hold it all together. I encountered the balafon, a similar instrument from Mali, north of Ghana, while studying with Jamal Mohamed. I was turned onto the gyil when preparing my senior recital at SMU. I corresponded with noted gyil performer Valerie Naranjo to learn about the instrument and in preparation for performance of "Nite Song," one of her marimba arrangements of traditional gyil music (I mentally arranged it back to gyil for my recital). My gyil (I have a pair) were purchased through the African Heartwood Project, which is a fair-trade organization helping artisans in Africa sell their work via the internet. (Track 6)

Ukulele - The ukulele is generally accepted to be the Hawaiian adaptation of a Portuguese instrument called "machete." It has been featured in pop music for many years, but was given legendary status through the music of Israel Kamakawiwo'ole (AKA "Iz"). He is the guy that improvised that "Over the Rainbow" we all cry when we hear. I love the music of Iz and I love the sound of the ukulele. It, like the cowboy's acoustic guitar, is an instrument made to sing with. The final track on the album features only my ukulele and my voice, and it was the instrument that inspired that particular song - I simply followed where it led. My ukulele was made by the Kala brand. (Track 7)

In some of my promotional materials I featured sarongs and saputs from Bali. These are traditional clothes used in ceremonies and in daily life by men and women (I think the saput might just be for guys). All of my sarongs and saputs are from Bali, purchased from local artisans or merchants. I have worn them to many Meadows World Music Ensemble (SMU) performances for their beauty and because they're actually really comfortable. I also used a Bondres mask in a music video. This is another type of Balinese mask that I purchased from its carver while in Bali. For more on Bondres masks, check out this page.

In summary, I am very much aware that cultural misappropriation is a bad thing. It involves taking advantage of people from less well-to-do cultures by using their arts and their creativity to turn a profit without providing any benefit to the original artists. I have done my very best to avoid this, and I believe I have been successful. I study the instruments and styles that I bring into my music and I am deeply passionate about building a global community of unique cultures joined together through compassion and understanding. None of the music on my album is "authentic," but rather the song styles are fusions of sounds, rhythms, and ideas from all over the world. This follows a tradition of artistic synthesis that goes back centuries, if not millenia, to the first time somebody met somebody else from out-of-town who had a cool new idea.

I hope you enjoy the album and are inspired to learn more about the people and cultures that inspired me!

Lawson

16 May 2020

Dallas, TX