1 - African Classical Music Ensemble & Kasse Made Diabate | There Was a Time | 2009

2 - Hugh Masekela | Still Grazing: The Musical Journey of Hugh Masekela | 1966-1974

3 - Hallelujah Chicken Run Band | Take One | 1974-1980

4 - Hurray for the Riff Raff | My Dearest Darkest Neighbor | 2013

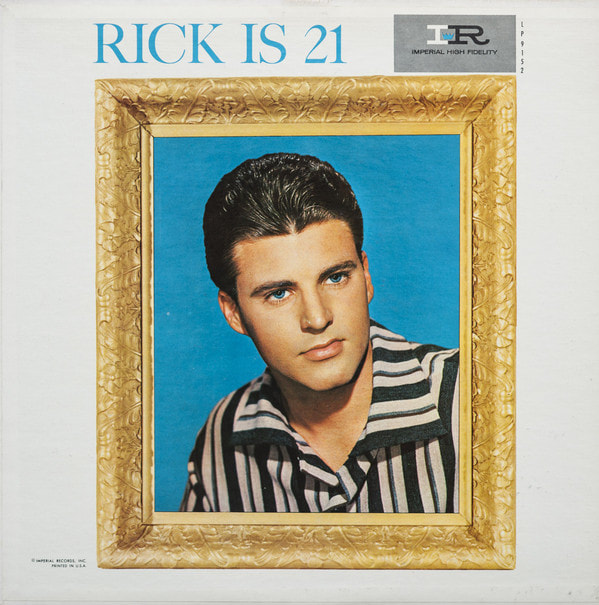

5 – Faces | Ooh La La | 1973

6 - Heartless Bastards | A Beautiful Life | 2021

7 – Tulus | Manusia | 2022

Maliq & D’essentials | RAYA | 2020

Kunto Aji | Mantra Mantra | 2018

Maliq & D’Essentials

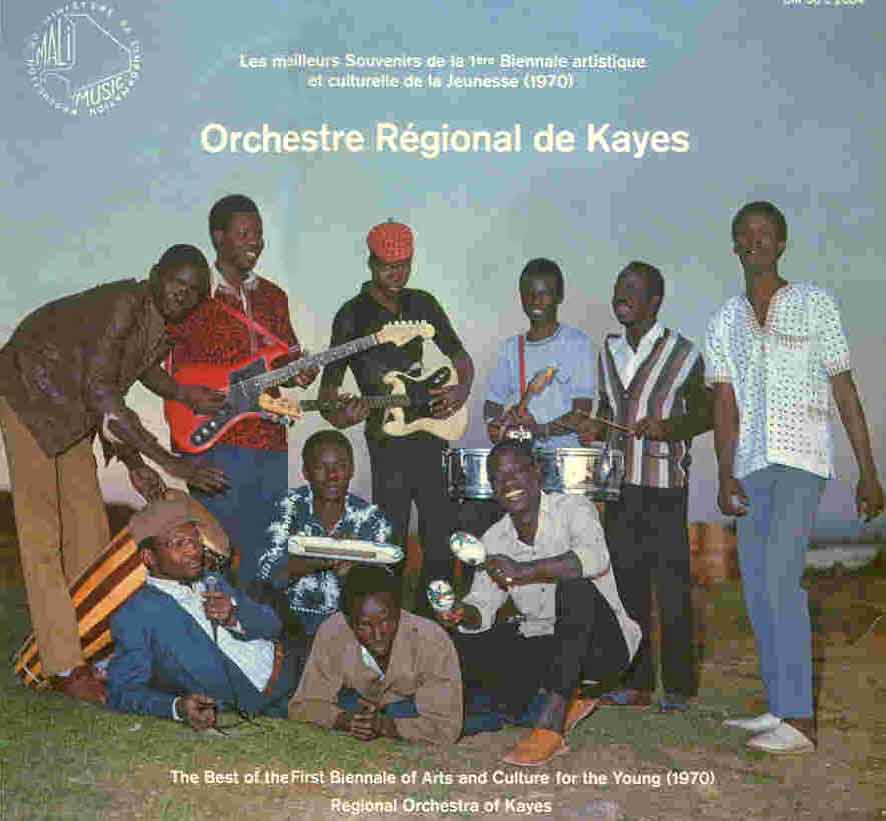

10 - Orchestre Régional de Kayes | Orchestra Régional de Kayes | 1970

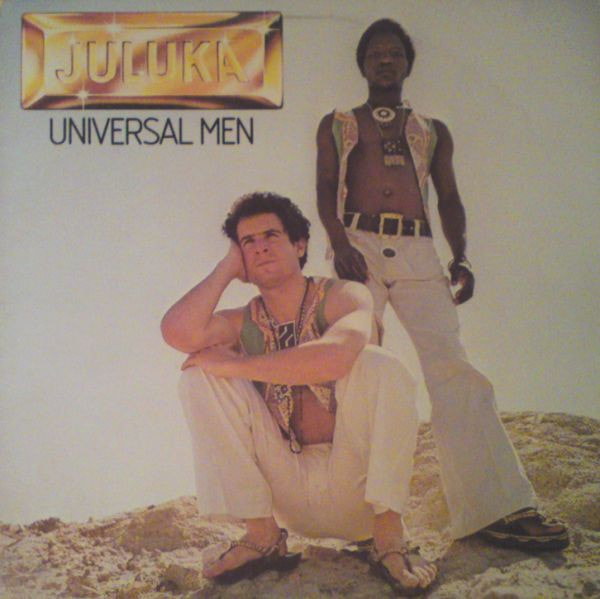

OOC – Juluka | Universal Men | 1979

I’m back with my Top 10 Albums list for the year 2023. If you haven’t been following along, here’s a refresher on how this works: instead of rating the top ten albums that were released this year, like the Grammy’s, Rolling Stone, BuzzFeed and the vast majority of bloggers and opinion writers you’ll hear from, I’m rating the top ten albums that I heard for my first time this year. I don’t keep up with contemporary pop, personally, because a lot of it is machine-manufactured and without artistry – the same thing sculptors would say about the $100 factory-made Julius Caesar bust on your desk and the same thing artisan weavers would say about your cheap mass-produced washable rug. If you want to save money and get affordable and immediate satisfaction, I won’t judge you for listening to today’s typical pop. But if you want good music – check out some of these.

Of course I’m not saying that no contemporary music is good – just look at the more recent entries on this list and the other Top 10s I shared the past few years. 2022 had an album from 2022 (by Natalia Lafourcade) and this year features a 2022, a 2021, and a 2020. But I also look further back in time for my lists and I reach farther out into the broader world of music, because while it’s easy for the music of Harry Styles to reach ears in Indonesia, it’s not nearly as easy for the music of contemporary Indonesian artists to reach the ears of Americans.

I would also like to take a moment to recommend that, if you have to stream your music, DON’T USE SPOTIFY. Spotify has regularly paid some of the lowest royalties to artists per-stream, and they are the ones who started the streaming craze and forced a lot of very creative people to move on from recording music because you don’t have a chance to make a living at it anymore. VIRPP ranked streaming payouts in 2023 and here are some data points:

Tidal: $0.01284 / stream (a little more than 1 cent)

Apple Music: $0.008 / stream (eight tenths of a cent)

Amazon Music: $0.00402 / stream (less than half a cent)

Spotify: $0.00318 / stream (piss)

(YouTube, Pandora, and Deezer all pay even less)

That said, let’s begin with Good Ovidius’ Top 10 Albums of 2023

Heard Out of Competition:

Juluka

Universal Men (1979)

Best Song: “Deliwe”

Universal Men isn’t rated in the Top 10 because technically speaking I had heard it before, back in 2021 or ’22, but it was on vinyl, and when I added the album to my Apple Music some of the songs weren’t included because there are different versions out there (Johnny Clegg albums can be labelled under his name or the names of the two different bands he was a part of, Juluka and Savuka, and the algorithms can struggle with this). Well in 2023 I finally heard the whole album over my car radio and really started getting to know it.

For me, this is some of Johnny Clegg’s best work. It was released in 1979 by Clegg and his long-time collaborator Sipho Mchunu under the bad name Juluka, which is Zulu for “Sweat.” Clegg was a white South African who spent a short while a history professor before launching his music career. He studied Zulu language, dance, and music and befriended many Zulu people, including Mchunu, and worked with members of the Zulu community to create a popular music style based on their own traditional musical language. Their live performances incorporated Zulu dance and costume, and over the years their work together was a major factor in bringing international attention to the Apartheid and ultimately ending it. Clegg was a leader of two different bands: Juluka (1979-1985) and Savuka (1986-1994; their song “Dela” was part of the soundtrack to George of the Jungle starring a young Brendan Frasier), and he had considerable solo success, but of all the work Clegg was involved in, Universal Men is some of the greatest.

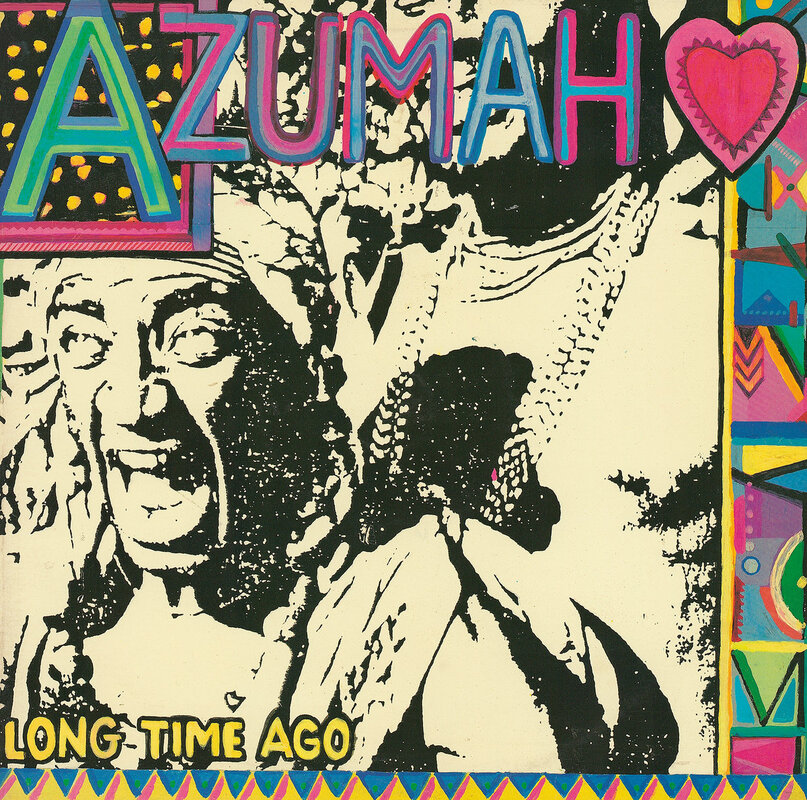

Before you even listen to the music, Juluka made several bold statements on the album cover. The one I will highlight for now is that the work “Juluka” (Zulu for sweat) is stamped on a bar of gold – the gold that was the source of the wealth that was extracted from South African mines via the sweat of the Zulu and other indigenous peoples.

Musically, the melodies and instrumentations are lush. Pulsing bass drums, twanging guitars, musical bows (look it up – it’s a string on a bent stick, like a bow for an arrow, plucked while held up to the mouth; the opening and shape of the mouth is adjusted to emphasize certain overtones of the bow’s vibration to create harmonized melodies), vocal harmonies – pretty much everything you could want in classic rock and then some with the addition of southern African influence.

The lyrics, however, are perhaps my favorite thing about this album and about Clegg’s work in general. Each song tells a story, and the way he does it - in this album in particular - shifting back and forth between Zulu and English, creating songs-within-songs, is beautiful. The title track, Universal Men, tells the story of the Zulu people, once proud, forced into a life of slavery living at the bottom of a society built by the labor of the indigenous people but designed for outsiders. The opening verse is revealed at the end of the song to be the mournful tune sung by the Zulu workers who are the “Universal Men” of the title.

But my favorite song on the album is “Deliwe” which translates to something like “rejected.” This one is sung by a guy trying to convince his lover not to go away to Europe by invoking all the things about home, her family, her heritage that she will leave behind when she goes. The chorus, sung first in Zulu, then in English, then in Zulu and then English again to close the song after the saxophone-solo bridge, is a prayer to the gods for protection (whether it’s a traditional prayer I do not know). When you translate the Zulu version, it’s not literally the same as the English version – it’s close - but the juxtaposition of the two with the same melody is fantastic. What really got me deep down amidst my heartstrings when I first heard the song this year – when I myself was in the middle of working through very painful heartbreak due to separation from someone I really cared about – was the final line of the pre-chorus, a doleful yet direct “oh Deliwe won’t you stay a while with me?” [Chorus drops here]

Transliteration of the chorus of “Deliwe” from the liner notes, shared with me by a member of the Johnny Clegg tribute page on facebook: Sicela kwabadala / besibhekele kulomhlaba / so’babongela

Translations of the two Zulu track titles: Unthando Luphelile – Love is Over | Inkunzi Ayihlabi Ngokumisa – The Bull Does Not Stop

Lyrics for another great song from the album, “Old Eyes” are here thanks to Cameron and Thembinkosi: https://www.chordie.com/chord.pere/www.guitaretab.com/j/juluka/270788.html

Number 10:

Orchestre Régional de Kayes

Orchestre Régional de Kayes (1970)

Best Song: “Sanjina”

I don’t know nearly as much about the history or context of the music of this album as I do about Clegg and Universal Men. Kayes is a city currently in western Mali, sitting on the Senegal River and relatively close to Mali’s border with Senegal the country. Mali, a former French colony and still an officially francophone country, covers a broad swathe of land and is home to many different groups of people with diverse and often unrelated traditions. Mali is the home of the wooden mallet keyboard instrument called the balafon and is perhaps best-known to modern musical audiences for the Mali Blues Guitar ensembles, like Tinariwen, that play traditional-esque melodies on electric guitar. The perceived relationship with American Blues music is not a coincidence, because the traditional music of Mali shares roots with the traditional music of many of the people who were kidnapped into slavery in the 18th and 19th centuries whose descendants developed the American Blues style. It’s not going back in a time machine and giving the ancestors of the Blues players an electric guitar, because those traditions have continued to develop in West Africa over the past few hundred years – instead it’s putting the electric guitar in music that shares centuries-old roots with the blues, and you still feel the connection.

This bit of history about the Orchestre Régional de Kayes comes from Radio Africa out of Australia ( https://www.radioafrica.com.au/Classics/Kayes.html )

“Kayes is situated on the Bamako-Dakar railway line in north-western Mali, just near the Senegalese border. The town is a regional capital of one of Mali's eight administrative regions. Shortly after independence Mali adopted a cultural policy which stipulated that a local orchestra must represent each region, hence the formation of the Kayes orchestra. Each year the orchestras would compete at the national arts festivals. Commencing in 1962, these "semaines" were held annually until the coup of 1968, whereafter they were held bi-annually and were known as the Biennales. At the arts festivals the Regional Orchestra of Kayes would compete against the other orchestras from Ségou, Tombouctou, Sikasso, Mopti, Gao, Koulikoro and Bamako for the championship prize. The above LP represents the orchestra's only recording - on the excellent Bärenreiter-Musicaphon series. It is a travesty that with the exception of a few tracks on the double-CD "Musiques du Mali vols 1 & 2" these seminal LPs have never been released on CD [This was written before the album became available for streaming]. They represent some of the finest modern music to have been recorded in West Africa. The Kayes orchestra were particularly outstanding, with arresting, searing guitar solos performed in classic Mandé songs such as "Duga" and "Malisajo". Some of the regional orchestras, such as those from Tombouctou, Gao and Koulikouro, missed out on being released through the Bärenreiter-Musicaphon series, but were recorded by Radio Mali, so there is certainly incentive for a wonderful series of re-issues...”

I first heard this album when I was visiting my dear friend the renowned composer Brandon Carson, who has written a lot of music for the also-amazing Dark Circles Contemporary Dance company. We both studied world music together for a few years and the funky-feeling rhythms of the melodies and humanist (as opposed to over-filtered & perfectionist) timbres of the voices and instruments brought me back to those times when our lives seemed a lot simpler, and the musical possibilities were endless. The opening track, “Sanjina” (possibly Bambara for “rain”) is a jazzy bop, but I’d say that my favorite is “Nanyuman” (again, possibly Bambara, for “afterwards”). An elegant guitar riff swirls around beneath the entire song while the vocals trade off with electric guitar expressions that would put the greatest American guitarists to shame while a saxophone hovers beneath, breathing heavily in anticipation of its starring role on the next track, “Duga”.

(Track title translations from Bambara via Google: Sanjina – The Rain | Kayi – Kayes (the city) | Nanyuman – Afterwards | Duga – Naïve | Malisajo (from Swahili)* – Pasture | Tèrèna – Terrain | Badage – Badges)

*Google’s Bambara translation of Malisajo was “Massage Therapist”

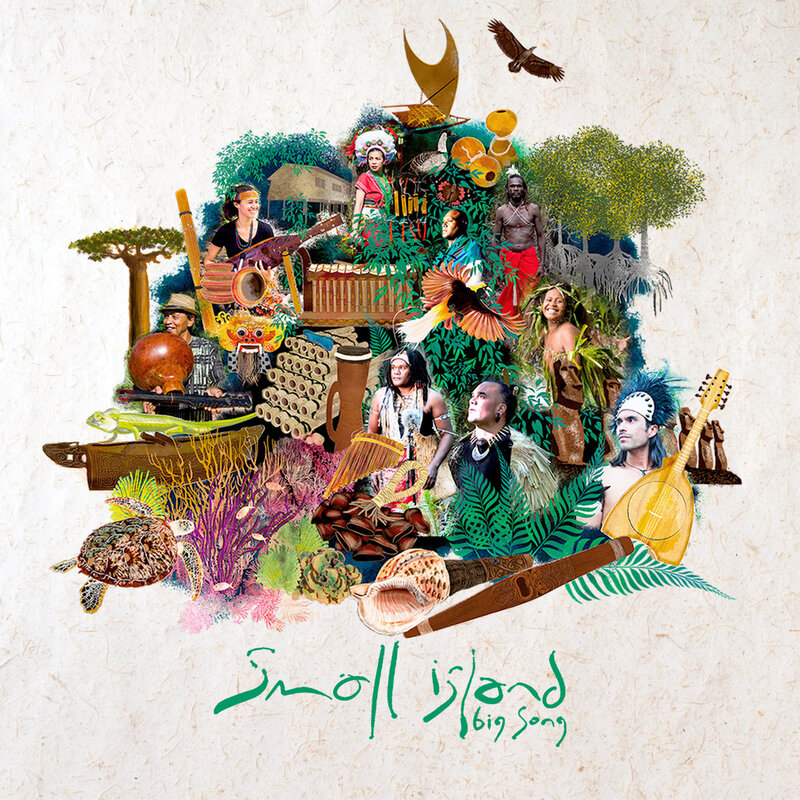

Number 7:

(Three-Way Tie)

Tulus – Manusia (2022) – Best Song: “Remedi”

Maliq & D’essentials – RAYA (2020) – Best Song:

Kunto Aji – Mantra Mantra (2018) – Best Song: “Saudade”

For Christmas 2021 my brother gave me a gift card for Half Price Books. I decided that, as a someone who claims to be familiar with a certain amount of Indonesian tradition (gamelan music and accompanying dance, Balinese masks, shadow puppets) I really needed to get on board with some of the more modern art. I figured one way I needed to broaden my perspective was through reading contemporary Indonesian novels. I got two – Saman, by a female author named Ayu Utami, which I read in early 2022 and was an amazing book; and Cantik Ita Luka (Beauty is a Wound) by male author Eka Kurniawan, which in part due to its greater length and its magical-realism dive into the past few hundred years of Indonesian history up to the present day, I found to be even more amazing. I wanted to live in that book, and I would be ready to go back and read it again any day. Part of what made the experience so intense was that for Kurniawan’s book I downloaded a few albums of contemporary Indonesian pop music to listen to while reading. These are my three favorites.

All of them carry hints of traditional music that I’ve heard (I am familiar mostly with Javanese and Balinese music, which are some of the most well-known traditions, but Java and Bali are only two of the 6,000 populated (out of 17,508 total) islands that make up Indonesia. All of them are also innovative in their own ways. I listed them here in the order they were released, and I’ll just highlight my favorite moments from each one.

Kunto Aji was born in 1987 in Slemen, near Yogyakarta, on the island of Java. He started his music career on Indonesian Idol in 2008, and Mantra Mantra is his second album. From opening of the first song on the album I was hooked. A delicately sung acapella melody in a musically tense pelog scale glides blissfully into lush vocal harmonies with a soft backbeat played on a single piano note. Then the guitar gently enters, and within a minute you’re transported to a sound world unlike anything you’ve probably ever heard before. My favorite song, “Saudade” (a Portuguese word describing the sense of loss and longing that is an innate part of being alive), opens with a beautiful synth-brass fanfare which establishes the general melody followed by the rest of the song (like the concept of Balungan, or “skeleton,” in Javanese gamelan music). The song, like the entire album, creates a soundscape wherein you can meditate and reflect on your own personal saudade until the end of time.

Track Titles translations from Indonesian via Google: Sulung – Eldest | Rencange Rencana – Design a Plan | Pilu Membiru – Sadness Turns Blue | Topik Semalam - Last Night’s Topic | Rehat – Take a Break | Jakarta Jakarta (Jakarta is the current capital of Indonesia) | Konon Katanya – It is Said | Saudade (this is a Portuguese word with no real English equivalent – it is close to “Longing” or in Indonesian “Kerinduan”) | Bungsu – Youngest (remember the name of the first track?)

Maliq & D’Essentials is a Jazz/Soul group that started in Jakarta, Java, in 2002. The music is complex, clean, and passionately inspired. And it’s damn good fun to listen to. Several months after I first listened through it, the chorus from “Good Lovin’” popped into my head one day. I went into my library to find the song and I was shocked to realize that it wasn’t one of the random American pop songs I heard playing at the bars all year – it’s so well-produced and in my opinion is very approachable for a typical American listener. I also love the incredible flow of the lyrics in “Memori” - Mulai hari ini / Janji-janji berterbangan menari / Yang terjadi ya terjadi saja / Karena cerita hari ini / Kemarin dan esok takkan terganti / Yang terjadi ya terjadi saja / Menjadi memori .

Track Titles translations from Indonesian via Google: Bertemu – Meet | Memori – Memory | Bilang – Said/Say | Good Lovin’ – Cinta Baik | Semoga – Hopefully | Sesuatunya – Something

Muhammed Tulus (stage name: Tulus) was born in 1987 in Bukittinggi on the island of Sumatra, Indonesia. Since 2016 he’s been a judge on The Voice Kids Indonesia. Manusia (Human) is his fourth album. It’s got a great combination of slow-paced and more upbeat songs. To me, the sound seems often to flow from retro-style intros into clean, modern verses, followed by almost Disney-esque choruses. I can picture Rafiki holding up Simba on Pride Rock during the high points of the opening track, and I can imagine the closing song showing up at that point in the stereotypical Disney movie where the hero is right on the verge of seeing everything fall apart before they need to put it back together – but for right now they’re still getting to celebrate how great this magical life is. My favorite song is “Remedi” (Remedy), and I might only care about the neo-noir horn opening. The rest of the song is great, but honestly I would like that little fanfare played at my funeral, on a loop, all the way through the whole ceremony.

Track Titles translations from Indonesian via Google: Tujuh Belas – Seventeen | Kelana – Wander | Remedi – Remedy | Interaksi – Interaction | Ingkar – Deny | Jatuh Suka – Fall in Love | Nala (a woman’s name) | Hati-Hati di Jalan – Be Careful on the Way (Hati-Hati is what they put on Caution signs in Indonesia, and Hati by itself can mean heart, psyche, etc.)| Diri – Self | Satu Kali – One Time

Number 6:

Heartless Bastards

A Beautiful Life (2021)

Best Song: “Doesn’t Matter Now”

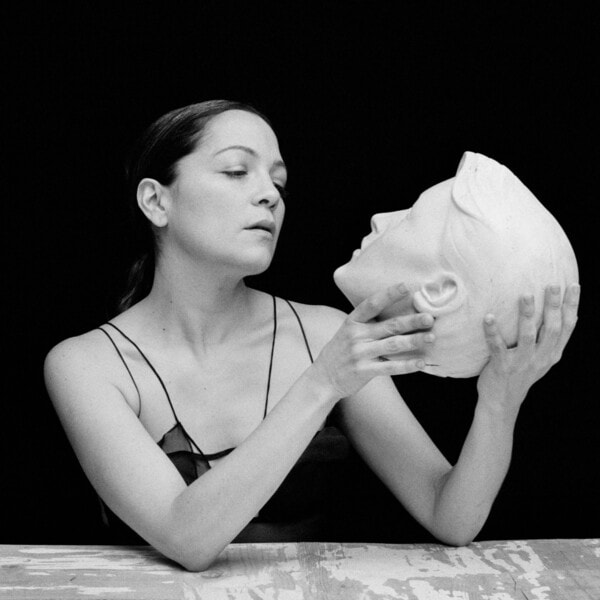

Heartless Bastards is a rock band out of Cincinnati Ohio fronted by lead singer Erika Wennerstrom. They’ve been going since 2003 and A Beautiful Life is their sixth full-length album. I’d heard music from their albums The Mountain (2009) and Arrow (2012) many years ago when you actually had to pay for music. In those days you could find bundles of “free samples” of indie music on various websites like NPR every once in a while.

I wanted to see what these heartless bastards were up to these days, and it turns out they’ve taken a turn for the optimistic – at least this latest album is more forthrightly so. If you’ll allow me to wax poetic, their earlier music seems pretty punk. A Beautiful Life sounds like those same punks a decade later became parents and realized instead of singing their punk lyrics they wanted to sound a little more positive for the sake of their kids.

But even with that shift, most of the same grit and style of Heartless Bastards is still there. The positivity is refreshing without making them bland, in my opinion. My favorite song, “Doesn’t Matter Now,” is incredibly simple in terms of lyrics (basically one verse and chorus that gets repeated, with a bridge thrown in there) and chords (according to Ultimate Guitar, the verse and chorus contain just two different chords), but that perfectly complements a importantly simple message about the importance of simply accepting and moving on. I read that one of the band’s motivations for this album was being a part of promoting reconciliation after the crises of 2020. That’s certainly a worthy cause and I think they nailed it.

Number 5:

Faces

Ooh La La (1973)

Best Song: “Ooh La La”

Speaking of Rod Stewart. I think everyone who has seen TV or been around social media sometime in the last five years is aware of the song “Ooh La La” (the album’s closing number) even if you don’t know it: “I wish, that, I knew what I know now, when I was younger” (everybody in the bar chants unmelodically as they try to remember how that song from whatever meme that is goes).

I have no idea where I heard it first but this Summer I was really vibing with that very sentence (which is the first line of the chorus), and I looked up the song. It turned out to be the very last song on the entire original studio discography of the British band Faces, which released only four albums during their original run from 1969-1975. Rod Stewart was the face of the band for most of that period of time, but towards the end was getting so famous for his solo work that their relationship strained. On this final album, his contributions were limited - the vocals for the title track are actually sung by Ronnie Wood, who joined the Rolling Stones shortly after Faces disbanded.

All of Faces’ music is classic blues-derived Rock & Roll, and I think this album is their peak and one of the best rock albums I’ve ever heard. It’s got a wonderful balance of contemplation and agitation, it’s thoughtfully produced (listen in stereo and pay attention to when the arrangement of different instruments, when they enter and where they are located in the sound-space), and it never seems to get old. I think the final one-two punch of “Just Another Honky” (featuring an unforgettable piano riff) and then “Ooh La La” (which could be the final word in any textbook on life and human nature” is one of the greatest closes to an album in the history of time. Go give it a listen.

Number 4:

Hurray for the Riff Raff

My Dearest Darkest Neighbor (2013)

Best Song: “People Talkin’”

I hear country music is becoming more popular. Oh wait, no – you’re actually talking about just more pop music, but it has a banjo and they’re singing about trucks and dogs. No offense to anyone who likes their folk music to include a lightshow, but when I want to hear about country, I go to places like Hurray for the Riff Raff. Gimme some god damn fiddle or it ain’t no country music.

Alynda Segarra, originally from New Orleans, has been releasing music under the name Hurray for the Riff Raff, in collaboration with various other extremely talented musicians, since 2008 – this was their fourth full-length album. Segarra’s music that I’ve heard consists of original songs that sound like they could have been sung in a saloon somewhere in Louisiana, or Texas, or Arizona, back the days of the wild west. The recording style pushes that sense that you’re listening to something truly old even further - it’s grainy and it sounds like they’re just recording live performances in a small room in a building made entirely of wood planks (which may well be exactly what they’re doing). The songs are about love, loss, and finding ways to be satisfied - and maybe even excited - about life, despite the disappointment it often turns out to be.

Segarra yodels, whispers, growls. The guitar licks are timeless, and the fiddling is bomb. Listen to Hurray for the Riff Raff, then go listen to Prince Albert Hunt’s Texas Ramblers (“Blues in a Bottle” from 1928 captures the earliest stages of the Texas Swing genre), and then check out Bob Wills and his Texas Playboys. These are that which passeth show.

Number 3:

Hallelujah Chicken Run Band

Take One (1974-1980)*

*Compilation of publishes singles, released in 2006

Best Song: “Alikulila”

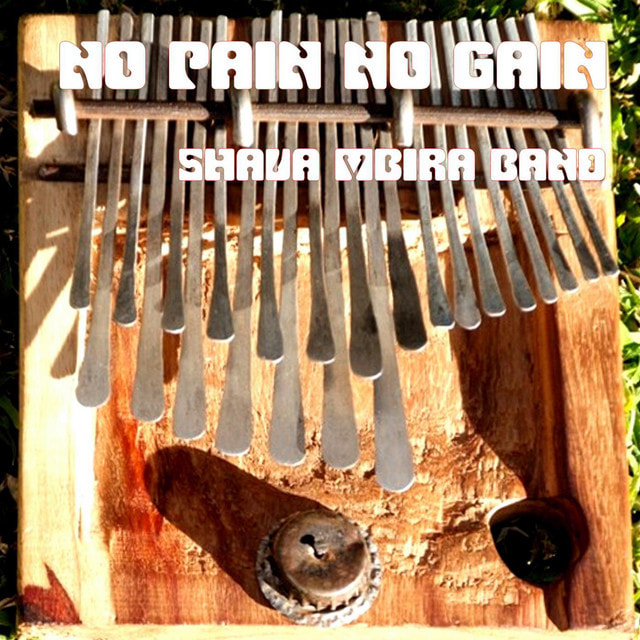

Thomas Mapfumo (born 1945 in Mazowe, Southern Rhodesia – now Zimbabwe) is called the father of Chimurenga music. “Chimurenga” is Shona for “struggle” and the word is used to refer to (a) the pair of revolutionary conflicts against the British colonial government that at long last resulted in an independent, self-ruled Zimbabwe in 1979 and (b) the style of music that fused rock & roll with traditional Shona instruments (primarily the several local forms of the thumb piano including the mbira dzavadzimu) and Shona songs – this music was the soundtrack of the Second Chimurenga (1967-1979) in a similar manner to which songs like “A Change is Gonna Come” were the soundtrack to the Civil Rights movement in the United States.

If Thomas Mapfumo (who I saw perform in the Student Center at SMU in 2016 – will always be one of the greatest concerts I got to witness) is the Father of Chimurenga, the rest of the members of the Hallelujah Chicken Run Band were the uncles. Mapfumo was the vocalist of this band that originally performed more generic African rock music in performances for copper mine workers. They eventually started to incorporate the mbira and traditional Shona songs and this new fusion took off. Thomas Mapfumo went on to record more than 20 albums with his band The Blacks Unlimited; traditional Shona mbira music has “gone global” with books, workshops, and Instagram pages on the subject; and hundreds of Zimbabwean musicians have been able to get their own recordings published – many performing very traditional music, and others, like the late Chiwoniso Maraire, evolving their traditional music in a new way to develop a totally unique style (her single, “Zvichapera” is one of the greatest records of all time and is a cover of a Thomas Mapfumo track).

Back in the ‘70s in Africa (and still for the US in some cases) the single was the dominant format for music releases – it would be played in the jukebox or over the radio. People didn’t buy their own copies all that often because it took a lot of expendable income to afford a personal record player. Take One is a compilation of all of the Hallelujah Chicken Run Band’s singles. Once again, I love this album for its balance. A lot of the songs are popping pepping dancing rock & rollers. But then other lay bare the suffering that took place under colonial role in Rhodesia and throughout southern Africa (Zimbabwe is the northern neighbor of South Africa, where the music of Juluka and Savuka fought against the Apartheid). If you listen closely to the instruments, you’ll hear just how ridiculously skillful the playing is – the intricate plucking on “Ngoma Yarira” and “Tamba Zimba Navasha,” and the peppy guitar part on “Tinokumbira Kuziva” that is joined by the icy-clean horn section. The recordings you hear are just snippets of what the songs would sound like in a love performance – each could go on for 10 minutes or more – it’s music for dancing plain and simple.

My favorite track, “Alikulila,” features a creeping bassline, understated call-and -esponse vocals, and one of the all-time great horn section melodies.

Track Title Translations from Shona via Google in tandem with my copy of the 1996 Standard Shona Dictionary: Mudzimu Ndiringe – The Spirit is Against Me | Kare Nanhasi – Past and Present | Tamba Zimba Navashe – Play House with the Lords | Ngoma Yarira – The Drum Beat | Sekai – Like | Manheru Changamire – Good Evening Sir | Gore Iro – That Year | Mukadzi Wangu Ndomuda – I Love My Wife | Alikulila (Arikurira) – He is Growing Up | Tinokumbira Kuziva – We Ask to Know | Mutoridodo (Mutorododo) – A Burden | Ndopenga – I’m Crazy | Mwana Wamai Dada Naye – My Cousin is Proud of Him | Chaminuka Mukuru – Chaminuka the Great (Chaminuka is an ancient mhondoro, an ancestral spirit who can still communicate with and lead the Shona through possessing living members of the community; perhaps the most famous medium through whom he spoke was Pasipamire Tsuro, who was a Shona leader in the late 19th century and foretold his peoples’ subjugation by Europeans and the century of suffering that would follow - more here)

Number 2:

Hugh Masekela

Still Grazing: The Musical Journey of Hugh Masekela (1966-1974)*

*Soundtrack to his 2004 autobiography

Best Song: “Been Such a Long Time Gone”

You’ve seen this commercial. That song is the great flugelhorn and trumpet player Hugh Masekela’s “Grazing in the Grass,” originally an instrumental composed by Philemon Hou and recorded first by Masekela in 1968 (Masekela also played cornet and was a kick ass singer). A year later it was also recorded by The Friends of Distinction with lyrics added – it became a hit that sold more than one million copies (again, back when you had to actually pay for music).

Of course, Masekela’s version was also a hit. Though that particular song was recorded in a studio in Hollywood, Masekela’s musical corpus, like the man himself is thoroughly and fundamentally South African. He lived from 1939-2018, was affectionately referred to as the “father of South African Jazz,” and like fellow South Africans Johnny Clegg, Sipho Mchunu, and the other members of Juluka and Savuka, helped fight for justice and human dignity with his music.

In 2004 he published an autobiography called Still Grazing: The Musical Story of Hugh Masekela, and like any self-respecting master musician should, he included a soundtrack with the book. This album is that soundtrack – Masekela’s own self-selected greatest hits recorded between 1966-1974. It has great variety – instrumentals like “A Felicidade,” “Up Up and Away,” and “Grazing in the Grass” are elevated examples of jazz and instrumental song – and Masekela’s actual songs (music with words – “songs” are sung) put masterful lyric-crafting talents on display. “Gold” shares basically the same message as Juluka’s Universal Men album cover – Gold pulled from the mountain to build wealth for the colonialists out of the sweat of the native people who don’t get to reap any of the benefits themselves. “Stimela” talks about the system of migrant labor – native South Africans forced to find work in mines far from their homes who ride the coal train (“stimela”) for their commute – complete with percussive vocalizations of steam-release sound effects.

My favorite song, without a doubt, is “Been Such a Long Time Gone.” I’m planning a Music That Moves short video focusing on this song so I won’t go too in-depth, but basically it takes you on a journey across Africa in the storyteller’s dream as he tries to get home to South Africa, but ultimately when he arrives at the border (the Limpopo river) he is shot by white soldiers who have claimed his home as their own. But “home” isn’t just the physical place – it’s a sense of identity, emotional safety, tradition – and that home is being kept from him in all its different senses. The lyrics are poetry and evoke stunning visual imagery, as he names and describes the rivers, valleys, and ecosystems he passes on his doomed journey home. There are a few other recordings of this song by Masekela available on Apple Music – I recommend listening to all of them so that you can hear how his voice and style changed over the years – and you can also hear what didn’t change and how he never lost a beat. Truly an all-time great.

Number 1:

African Classical Music Ensemble & Kasse Made Diabate

There Was a Time (2009)

Best Song: “Sundiata”

Kasse Made Diabate (1949-2018) was a musician from Mali. He was a griot – a member of a hereditary profession responsible for tracking history orally and for recounting (hi)stories through poetry and song. He sang with a group led by his brother Abdoulaye Diabate called Super Mande, and in 1973 they won the Biennale festival (see Orchestre Régional de Kayes section in this same article). He went on to have an incredible career and work with some of the greatest musical artists of his time. The African Classical Music Ensemble was started by Malian musician Tunde Jegede “to celebrate the distinct acoustic classical musical traditions of Africa,” and consists of Jegede himself along with Juldeh Camara and Sona Maya Jobarteh. They’re collaborated with a number of other great artists in addition to Kasse Made Diabate.

From ACME’s website: “There Was A Time is a timeless album that touches on an ancient sound within a contemporary setting. This is completely acoustic Malian music at its very best. The soaring voice of Kassé Mady takes us back to time immemorial where past and present submerge. The lyricism of this album is a living testament to the inherent classicism of this music in its original form. It is a music that creates feelings of joy and melancholy in a single moment. There Was A Time brings us back to the time of our earliest memories.”

I agree – this music is incredible. Any words I could say about it here would be a “nothing burger” – words for the sake of words that really don’t contribute anything. Please just go listen to this album.

My favorite song is Sundiata – it’s the collaborative group’s take on a traditional song named after the great Sundiata Keita – founder of the Mali empire which was ruled about 100 years later by his great-nephew Mansa Musa, who is believed to be the wealthiest person in the history of the world. This song contains the wealthiest flute solo of all time, played on a Malinke style flute (see it in action). Unfortunately, I haven’t been able to figure out exactly who is playing the flute on this recording. Whoever it is deserves a Nobel Peace Prize. Put this song on your biggest, best speaker; turn out every single light in your house; and just lie there on the floor and enjoy this masterpiece. When you open your eyes again you will be living in a world where it really is possible to put the greater good ahead of your own benefit – where it’s possible for peace and friendship to win out over greed – where dreams, really do come true.

That’s it for Good Ovidius’ Top 10 Albums of 2023. I hope you have as much fun listening to these albums this year as I did listening to them last year.

Sincerely,

Lawson

17 January 2024

Downtown Phoenix, AZ

2 - Hugh Masekela | Still Grazing: The Musical Journey of Hugh Masekela | 1966-1974

3 - Hallelujah Chicken Run Band | Take One | 1974-1980

4 - Hurray for the Riff Raff | My Dearest Darkest Neighbor | 2013

5 – Faces | Ooh La La | 1973

6 - Heartless Bastards | A Beautiful Life | 2021

7 – Tulus | Manusia | 2022

Maliq & D’essentials | RAYA | 2020

Kunto Aji | Mantra Mantra | 2018

Maliq & D’Essentials

10 - Orchestre Régional de Kayes | Orchestra Régional de Kayes | 1970

OOC – Juluka | Universal Men | 1979

I’m back with my Top 10 Albums list for the year 2023. If you haven’t been following along, here’s a refresher on how this works: instead of rating the top ten albums that were released this year, like the Grammy’s, Rolling Stone, BuzzFeed and the vast majority of bloggers and opinion writers you’ll hear from, I’m rating the top ten albums that I heard for my first time this year. I don’t keep up with contemporary pop, personally, because a lot of it is machine-manufactured and without artistry – the same thing sculptors would say about the $100 factory-made Julius Caesar bust on your desk and the same thing artisan weavers would say about your cheap mass-produced washable rug. If you want to save money and get affordable and immediate satisfaction, I won’t judge you for listening to today’s typical pop. But if you want good music – check out some of these.

Of course I’m not saying that no contemporary music is good – just look at the more recent entries on this list and the other Top 10s I shared the past few years. 2022 had an album from 2022 (by Natalia Lafourcade) and this year features a 2022, a 2021, and a 2020. But I also look further back in time for my lists and I reach farther out into the broader world of music, because while it’s easy for the music of Harry Styles to reach ears in Indonesia, it’s not nearly as easy for the music of contemporary Indonesian artists to reach the ears of Americans.

I would also like to take a moment to recommend that, if you have to stream your music, DON’T USE SPOTIFY. Spotify has regularly paid some of the lowest royalties to artists per-stream, and they are the ones who started the streaming craze and forced a lot of very creative people to move on from recording music because you don’t have a chance to make a living at it anymore. VIRPP ranked streaming payouts in 2023 and here are some data points:

Tidal: $0.01284 / stream (a little more than 1 cent)

Apple Music: $0.008 / stream (eight tenths of a cent)

Amazon Music: $0.00402 / stream (less than half a cent)

Spotify: $0.00318 / stream (piss)

(YouTube, Pandora, and Deezer all pay even less)

That said, let’s begin with Good Ovidius’ Top 10 Albums of 2023

Heard Out of Competition:

Juluka

Universal Men (1979)

Best Song: “Deliwe”

Universal Men isn’t rated in the Top 10 because technically speaking I had heard it before, back in 2021 or ’22, but it was on vinyl, and when I added the album to my Apple Music some of the songs weren’t included because there are different versions out there (Johnny Clegg albums can be labelled under his name or the names of the two different bands he was a part of, Juluka and Savuka, and the algorithms can struggle with this). Well in 2023 I finally heard the whole album over my car radio and really started getting to know it.

For me, this is some of Johnny Clegg’s best work. It was released in 1979 by Clegg and his long-time collaborator Sipho Mchunu under the bad name Juluka, which is Zulu for “Sweat.” Clegg was a white South African who spent a short while a history professor before launching his music career. He studied Zulu language, dance, and music and befriended many Zulu people, including Mchunu, and worked with members of the Zulu community to create a popular music style based on their own traditional musical language. Their live performances incorporated Zulu dance and costume, and over the years their work together was a major factor in bringing international attention to the Apartheid and ultimately ending it. Clegg was a leader of two different bands: Juluka (1979-1985) and Savuka (1986-1994; their song “Dela” was part of the soundtrack to George of the Jungle starring a young Brendan Frasier), and he had considerable solo success, but of all the work Clegg was involved in, Universal Men is some of the greatest.

Before you even listen to the music, Juluka made several bold statements on the album cover. The one I will highlight for now is that the work “Juluka” (Zulu for sweat) is stamped on a bar of gold – the gold that was the source of the wealth that was extracted from South African mines via the sweat of the Zulu and other indigenous peoples.

Musically, the melodies and instrumentations are lush. Pulsing bass drums, twanging guitars, musical bows (look it up – it’s a string on a bent stick, like a bow for an arrow, plucked while held up to the mouth; the opening and shape of the mouth is adjusted to emphasize certain overtones of the bow’s vibration to create harmonized melodies), vocal harmonies – pretty much everything you could want in classic rock and then some with the addition of southern African influence.

The lyrics, however, are perhaps my favorite thing about this album and about Clegg’s work in general. Each song tells a story, and the way he does it - in this album in particular - shifting back and forth between Zulu and English, creating songs-within-songs, is beautiful. The title track, Universal Men, tells the story of the Zulu people, once proud, forced into a life of slavery living at the bottom of a society built by the labor of the indigenous people but designed for outsiders. The opening verse is revealed at the end of the song to be the mournful tune sung by the Zulu workers who are the “Universal Men” of the title.

But my favorite song on the album is “Deliwe” which translates to something like “rejected.” This one is sung by a guy trying to convince his lover not to go away to Europe by invoking all the things about home, her family, her heritage that she will leave behind when she goes. The chorus, sung first in Zulu, then in English, then in Zulu and then English again to close the song after the saxophone-solo bridge, is a prayer to the gods for protection (whether it’s a traditional prayer I do not know). When you translate the Zulu version, it’s not literally the same as the English version – it’s close - but the juxtaposition of the two with the same melody is fantastic. What really got me deep down amidst my heartstrings when I first heard the song this year – when I myself was in the middle of working through very painful heartbreak due to separation from someone I really cared about – was the final line of the pre-chorus, a doleful yet direct “oh Deliwe won’t you stay a while with me?” [Chorus drops here]

Transliteration of the chorus of “Deliwe” from the liner notes, shared with me by a member of the Johnny Clegg tribute page on facebook: Sicela kwabadala / besibhekele kulomhlaba / so’babongela

Translations of the two Zulu track titles: Unthando Luphelile – Love is Over | Inkunzi Ayihlabi Ngokumisa – The Bull Does Not Stop

Lyrics for another great song from the album, “Old Eyes” are here thanks to Cameron and Thembinkosi: https://www.chordie.com/chord.pere/www.guitaretab.com/j/juluka/270788.html

Number 10:

Orchestre Régional de Kayes

Orchestre Régional de Kayes (1970)

Best Song: “Sanjina”

I don’t know nearly as much about the history or context of the music of this album as I do about Clegg and Universal Men. Kayes is a city currently in western Mali, sitting on the Senegal River and relatively close to Mali’s border with Senegal the country. Mali, a former French colony and still an officially francophone country, covers a broad swathe of land and is home to many different groups of people with diverse and often unrelated traditions. Mali is the home of the wooden mallet keyboard instrument called the balafon and is perhaps best-known to modern musical audiences for the Mali Blues Guitar ensembles, like Tinariwen, that play traditional-esque melodies on electric guitar. The perceived relationship with American Blues music is not a coincidence, because the traditional music of Mali shares roots with the traditional music of many of the people who were kidnapped into slavery in the 18th and 19th centuries whose descendants developed the American Blues style. It’s not going back in a time machine and giving the ancestors of the Blues players an electric guitar, because those traditions have continued to develop in West Africa over the past few hundred years – instead it’s putting the electric guitar in music that shares centuries-old roots with the blues, and you still feel the connection.

This bit of history about the Orchestre Régional de Kayes comes from Radio Africa out of Australia ( https://www.radioafrica.com.au/Classics/Kayes.html )

“Kayes is situated on the Bamako-Dakar railway line in north-western Mali, just near the Senegalese border. The town is a regional capital of one of Mali's eight administrative regions. Shortly after independence Mali adopted a cultural policy which stipulated that a local orchestra must represent each region, hence the formation of the Kayes orchestra. Each year the orchestras would compete at the national arts festivals. Commencing in 1962, these "semaines" were held annually until the coup of 1968, whereafter they were held bi-annually and were known as the Biennales. At the arts festivals the Regional Orchestra of Kayes would compete against the other orchestras from Ségou, Tombouctou, Sikasso, Mopti, Gao, Koulikoro and Bamako for the championship prize. The above LP represents the orchestra's only recording - on the excellent Bärenreiter-Musicaphon series. It is a travesty that with the exception of a few tracks on the double-CD "Musiques du Mali vols 1 & 2" these seminal LPs have never been released on CD [This was written before the album became available for streaming]. They represent some of the finest modern music to have been recorded in West Africa. The Kayes orchestra were particularly outstanding, with arresting, searing guitar solos performed in classic Mandé songs such as "Duga" and "Malisajo". Some of the regional orchestras, such as those from Tombouctou, Gao and Koulikouro, missed out on being released through the Bärenreiter-Musicaphon series, but were recorded by Radio Mali, so there is certainly incentive for a wonderful series of re-issues...”

I first heard this album when I was visiting my dear friend the renowned composer Brandon Carson, who has written a lot of music for the also-amazing Dark Circles Contemporary Dance company. We both studied world music together for a few years and the funky-feeling rhythms of the melodies and humanist (as opposed to over-filtered & perfectionist) timbres of the voices and instruments brought me back to those times when our lives seemed a lot simpler, and the musical possibilities were endless. The opening track, “Sanjina” (possibly Bambara for “rain”) is a jazzy bop, but I’d say that my favorite is “Nanyuman” (again, possibly Bambara, for “afterwards”). An elegant guitar riff swirls around beneath the entire song while the vocals trade off with electric guitar expressions that would put the greatest American guitarists to shame while a saxophone hovers beneath, breathing heavily in anticipation of its starring role on the next track, “Duga”.

(Track title translations from Bambara via Google: Sanjina – The Rain | Kayi – Kayes (the city) | Nanyuman – Afterwards | Duga – Naïve | Malisajo (from Swahili)* – Pasture | Tèrèna – Terrain | Badage – Badges)

*Google’s Bambara translation of Malisajo was “Massage Therapist”

Number 7:

(Three-Way Tie)

Tulus – Manusia (2022) – Best Song: “Remedi”

Maliq & D’essentials – RAYA (2020) – Best Song:

Kunto Aji – Mantra Mantra (2018) – Best Song: “Saudade”

For Christmas 2021 my brother gave me a gift card for Half Price Books. I decided that, as a someone who claims to be familiar with a certain amount of Indonesian tradition (gamelan music and accompanying dance, Balinese masks, shadow puppets) I really needed to get on board with some of the more modern art. I figured one way I needed to broaden my perspective was through reading contemporary Indonesian novels. I got two – Saman, by a female author named Ayu Utami, which I read in early 2022 and was an amazing book; and Cantik Ita Luka (Beauty is a Wound) by male author Eka Kurniawan, which in part due to its greater length and its magical-realism dive into the past few hundred years of Indonesian history up to the present day, I found to be even more amazing. I wanted to live in that book, and I would be ready to go back and read it again any day. Part of what made the experience so intense was that for Kurniawan’s book I downloaded a few albums of contemporary Indonesian pop music to listen to while reading. These are my three favorites.

All of them carry hints of traditional music that I’ve heard (I am familiar mostly with Javanese and Balinese music, which are some of the most well-known traditions, but Java and Bali are only two of the 6,000 populated (out of 17,508 total) islands that make up Indonesia. All of them are also innovative in their own ways. I listed them here in the order they were released, and I’ll just highlight my favorite moments from each one.

Kunto Aji was born in 1987 in Slemen, near Yogyakarta, on the island of Java. He started his music career on Indonesian Idol in 2008, and Mantra Mantra is his second album. From opening of the first song on the album I was hooked. A delicately sung acapella melody in a musically tense pelog scale glides blissfully into lush vocal harmonies with a soft backbeat played on a single piano note. Then the guitar gently enters, and within a minute you’re transported to a sound world unlike anything you’ve probably ever heard before. My favorite song, “Saudade” (a Portuguese word describing the sense of loss and longing that is an innate part of being alive), opens with a beautiful synth-brass fanfare which establishes the general melody followed by the rest of the song (like the concept of Balungan, or “skeleton,” in Javanese gamelan music). The song, like the entire album, creates a soundscape wherein you can meditate and reflect on your own personal saudade until the end of time.

Track Titles translations from Indonesian via Google: Sulung – Eldest | Rencange Rencana – Design a Plan | Pilu Membiru – Sadness Turns Blue | Topik Semalam - Last Night’s Topic | Rehat – Take a Break | Jakarta Jakarta (Jakarta is the current capital of Indonesia) | Konon Katanya – It is Said | Saudade (this is a Portuguese word with no real English equivalent – it is close to “Longing” or in Indonesian “Kerinduan”) | Bungsu – Youngest (remember the name of the first track?)

Maliq & D’Essentials is a Jazz/Soul group that started in Jakarta, Java, in 2002. The music is complex, clean, and passionately inspired. And it’s damn good fun to listen to. Several months after I first listened through it, the chorus from “Good Lovin’” popped into my head one day. I went into my library to find the song and I was shocked to realize that it wasn’t one of the random American pop songs I heard playing at the bars all year – it’s so well-produced and in my opinion is very approachable for a typical American listener. I also love the incredible flow of the lyrics in “Memori” - Mulai hari ini / Janji-janji berterbangan menari / Yang terjadi ya terjadi saja / Karena cerita hari ini / Kemarin dan esok takkan terganti / Yang terjadi ya terjadi saja / Menjadi memori .

Track Titles translations from Indonesian via Google: Bertemu – Meet | Memori – Memory | Bilang – Said/Say | Good Lovin’ – Cinta Baik | Semoga – Hopefully | Sesuatunya – Something

Muhammed Tulus (stage name: Tulus) was born in 1987 in Bukittinggi on the island of Sumatra, Indonesia. Since 2016 he’s been a judge on The Voice Kids Indonesia. Manusia (Human) is his fourth album. It’s got a great combination of slow-paced and more upbeat songs. To me, the sound seems often to flow from retro-style intros into clean, modern verses, followed by almost Disney-esque choruses. I can picture Rafiki holding up Simba on Pride Rock during the high points of the opening track, and I can imagine the closing song showing up at that point in the stereotypical Disney movie where the hero is right on the verge of seeing everything fall apart before they need to put it back together – but for right now they’re still getting to celebrate how great this magical life is. My favorite song is “Remedi” (Remedy), and I might only care about the neo-noir horn opening. The rest of the song is great, but honestly I would like that little fanfare played at my funeral, on a loop, all the way through the whole ceremony.

Track Titles translations from Indonesian via Google: Tujuh Belas – Seventeen | Kelana – Wander | Remedi – Remedy | Interaksi – Interaction | Ingkar – Deny | Jatuh Suka – Fall in Love | Nala (a woman’s name) | Hati-Hati di Jalan – Be Careful on the Way (Hati-Hati is what they put on Caution signs in Indonesia, and Hati by itself can mean heart, psyche, etc.)| Diri – Self | Satu Kali – One Time

Number 6:

Heartless Bastards

A Beautiful Life (2021)

Best Song: “Doesn’t Matter Now”

Heartless Bastards is a rock band out of Cincinnati Ohio fronted by lead singer Erika Wennerstrom. They’ve been going since 2003 and A Beautiful Life is their sixth full-length album. I’d heard music from their albums The Mountain (2009) and Arrow (2012) many years ago when you actually had to pay for music. In those days you could find bundles of “free samples” of indie music on various websites like NPR every once in a while.

I wanted to see what these heartless bastards were up to these days, and it turns out they’ve taken a turn for the optimistic – at least this latest album is more forthrightly so. If you’ll allow me to wax poetic, their earlier music seems pretty punk. A Beautiful Life sounds like those same punks a decade later became parents and realized instead of singing their punk lyrics they wanted to sound a little more positive for the sake of their kids.

But even with that shift, most of the same grit and style of Heartless Bastards is still there. The positivity is refreshing without making them bland, in my opinion. My favorite song, “Doesn’t Matter Now,” is incredibly simple in terms of lyrics (basically one verse and chorus that gets repeated, with a bridge thrown in there) and chords (according to Ultimate Guitar, the verse and chorus contain just two different chords), but that perfectly complements a importantly simple message about the importance of simply accepting and moving on. I read that one of the band’s motivations for this album was being a part of promoting reconciliation after the crises of 2020. That’s certainly a worthy cause and I think they nailed it.

Number 5:

Faces

Ooh La La (1973)

Best Song: “Ooh La La”

Speaking of Rod Stewart. I think everyone who has seen TV or been around social media sometime in the last five years is aware of the song “Ooh La La” (the album’s closing number) even if you don’t know it: “I wish, that, I knew what I know now, when I was younger” (everybody in the bar chants unmelodically as they try to remember how that song from whatever meme that is goes).

I have no idea where I heard it first but this Summer I was really vibing with that very sentence (which is the first line of the chorus), and I looked up the song. It turned out to be the very last song on the entire original studio discography of the British band Faces, which released only four albums during their original run from 1969-1975. Rod Stewart was the face of the band for most of that period of time, but towards the end was getting so famous for his solo work that their relationship strained. On this final album, his contributions were limited - the vocals for the title track are actually sung by Ronnie Wood, who joined the Rolling Stones shortly after Faces disbanded.

All of Faces’ music is classic blues-derived Rock & Roll, and I think this album is their peak and one of the best rock albums I’ve ever heard. It’s got a wonderful balance of contemplation and agitation, it’s thoughtfully produced (listen in stereo and pay attention to when the arrangement of different instruments, when they enter and where they are located in the sound-space), and it never seems to get old. I think the final one-two punch of “Just Another Honky” (featuring an unforgettable piano riff) and then “Ooh La La” (which could be the final word in any textbook on life and human nature” is one of the greatest closes to an album in the history of time. Go give it a listen.

Number 4:

Hurray for the Riff Raff

My Dearest Darkest Neighbor (2013)

Best Song: “People Talkin’”

I hear country music is becoming more popular. Oh wait, no – you’re actually talking about just more pop music, but it has a banjo and they’re singing about trucks and dogs. No offense to anyone who likes their folk music to include a lightshow, but when I want to hear about country, I go to places like Hurray for the Riff Raff. Gimme some god damn fiddle or it ain’t no country music.

Alynda Segarra, originally from New Orleans, has been releasing music under the name Hurray for the Riff Raff, in collaboration with various other extremely talented musicians, since 2008 – this was their fourth full-length album. Segarra’s music that I’ve heard consists of original songs that sound like they could have been sung in a saloon somewhere in Louisiana, or Texas, or Arizona, back the days of the wild west. The recording style pushes that sense that you’re listening to something truly old even further - it’s grainy and it sounds like they’re just recording live performances in a small room in a building made entirely of wood planks (which may well be exactly what they’re doing). The songs are about love, loss, and finding ways to be satisfied - and maybe even excited - about life, despite the disappointment it often turns out to be.

Segarra yodels, whispers, growls. The guitar licks are timeless, and the fiddling is bomb. Listen to Hurray for the Riff Raff, then go listen to Prince Albert Hunt’s Texas Ramblers (“Blues in a Bottle” from 1928 captures the earliest stages of the Texas Swing genre), and then check out Bob Wills and his Texas Playboys. These are that which passeth show.

Number 3:

Hallelujah Chicken Run Band

Take One (1974-1980)*

*Compilation of publishes singles, released in 2006

Best Song: “Alikulila”

Thomas Mapfumo (born 1945 in Mazowe, Southern Rhodesia – now Zimbabwe) is called the father of Chimurenga music. “Chimurenga” is Shona for “struggle” and the word is used to refer to (a) the pair of revolutionary conflicts against the British colonial government that at long last resulted in an independent, self-ruled Zimbabwe in 1979 and (b) the style of music that fused rock & roll with traditional Shona instruments (primarily the several local forms of the thumb piano including the mbira dzavadzimu) and Shona songs – this music was the soundtrack of the Second Chimurenga (1967-1979) in a similar manner to which songs like “A Change is Gonna Come” were the soundtrack to the Civil Rights movement in the United States.

If Thomas Mapfumo (who I saw perform in the Student Center at SMU in 2016 – will always be one of the greatest concerts I got to witness) is the Father of Chimurenga, the rest of the members of the Hallelujah Chicken Run Band were the uncles. Mapfumo was the vocalist of this band that originally performed more generic African rock music in performances for copper mine workers. They eventually started to incorporate the mbira and traditional Shona songs and this new fusion took off. Thomas Mapfumo went on to record more than 20 albums with his band The Blacks Unlimited; traditional Shona mbira music has “gone global” with books, workshops, and Instagram pages on the subject; and hundreds of Zimbabwean musicians have been able to get their own recordings published – many performing very traditional music, and others, like the late Chiwoniso Maraire, evolving their traditional music in a new way to develop a totally unique style (her single, “Zvichapera” is one of the greatest records of all time and is a cover of a Thomas Mapfumo track).

Back in the ‘70s in Africa (and still for the US in some cases) the single was the dominant format for music releases – it would be played in the jukebox or over the radio. People didn’t buy their own copies all that often because it took a lot of expendable income to afford a personal record player. Take One is a compilation of all of the Hallelujah Chicken Run Band’s singles. Once again, I love this album for its balance. A lot of the songs are popping pepping dancing rock & rollers. But then other lay bare the suffering that took place under colonial role in Rhodesia and throughout southern Africa (Zimbabwe is the northern neighbor of South Africa, where the music of Juluka and Savuka fought against the Apartheid). If you listen closely to the instruments, you’ll hear just how ridiculously skillful the playing is – the intricate plucking on “Ngoma Yarira” and “Tamba Zimba Navasha,” and the peppy guitar part on “Tinokumbira Kuziva” that is joined by the icy-clean horn section. The recordings you hear are just snippets of what the songs would sound like in a love performance – each could go on for 10 minutes or more – it’s music for dancing plain and simple.

My favorite track, “Alikulila,” features a creeping bassline, understated call-and -esponse vocals, and one of the all-time great horn section melodies.

Track Title Translations from Shona via Google in tandem with my copy of the 1996 Standard Shona Dictionary: Mudzimu Ndiringe – The Spirit is Against Me | Kare Nanhasi – Past and Present | Tamba Zimba Navashe – Play House with the Lords | Ngoma Yarira – The Drum Beat | Sekai – Like | Manheru Changamire – Good Evening Sir | Gore Iro – That Year | Mukadzi Wangu Ndomuda – I Love My Wife | Alikulila (Arikurira) – He is Growing Up | Tinokumbira Kuziva – We Ask to Know | Mutoridodo (Mutorododo) – A Burden | Ndopenga – I’m Crazy | Mwana Wamai Dada Naye – My Cousin is Proud of Him | Chaminuka Mukuru – Chaminuka the Great (Chaminuka is an ancient mhondoro, an ancestral spirit who can still communicate with and lead the Shona through possessing living members of the community; perhaps the most famous medium through whom he spoke was Pasipamire Tsuro, who was a Shona leader in the late 19th century and foretold his peoples’ subjugation by Europeans and the century of suffering that would follow - more here)

Number 2:

Hugh Masekela

Still Grazing: The Musical Journey of Hugh Masekela (1966-1974)*

*Soundtrack to his 2004 autobiography

Best Song: “Been Such a Long Time Gone”

You’ve seen this commercial. That song is the great flugelhorn and trumpet player Hugh Masekela’s “Grazing in the Grass,” originally an instrumental composed by Philemon Hou and recorded first by Masekela in 1968 (Masekela also played cornet and was a kick ass singer). A year later it was also recorded by The Friends of Distinction with lyrics added – it became a hit that sold more than one million copies (again, back when you had to actually pay for music).

Of course, Masekela’s version was also a hit. Though that particular song was recorded in a studio in Hollywood, Masekela’s musical corpus, like the man himself is thoroughly and fundamentally South African. He lived from 1939-2018, was affectionately referred to as the “father of South African Jazz,” and like fellow South Africans Johnny Clegg, Sipho Mchunu, and the other members of Juluka and Savuka, helped fight for justice and human dignity with his music.

In 2004 he published an autobiography called Still Grazing: The Musical Story of Hugh Masekela, and like any self-respecting master musician should, he included a soundtrack with the book. This album is that soundtrack – Masekela’s own self-selected greatest hits recorded between 1966-1974. It has great variety – instrumentals like “A Felicidade,” “Up Up and Away,” and “Grazing in the Grass” are elevated examples of jazz and instrumental song – and Masekela’s actual songs (music with words – “songs” are sung) put masterful lyric-crafting talents on display. “Gold” shares basically the same message as Juluka’s Universal Men album cover – Gold pulled from the mountain to build wealth for the colonialists out of the sweat of the native people who don’t get to reap any of the benefits themselves. “Stimela” talks about the system of migrant labor – native South Africans forced to find work in mines far from their homes who ride the coal train (“stimela”) for their commute – complete with percussive vocalizations of steam-release sound effects.

My favorite song, without a doubt, is “Been Such a Long Time Gone.” I’m planning a Music That Moves short video focusing on this song so I won’t go too in-depth, but basically it takes you on a journey across Africa in the storyteller’s dream as he tries to get home to South Africa, but ultimately when he arrives at the border (the Limpopo river) he is shot by white soldiers who have claimed his home as their own. But “home” isn’t just the physical place – it’s a sense of identity, emotional safety, tradition – and that home is being kept from him in all its different senses. The lyrics are poetry and evoke stunning visual imagery, as he names and describes the rivers, valleys, and ecosystems he passes on his doomed journey home. There are a few other recordings of this song by Masekela available on Apple Music – I recommend listening to all of them so that you can hear how his voice and style changed over the years – and you can also hear what didn’t change and how he never lost a beat. Truly an all-time great.

Number 1:

African Classical Music Ensemble & Kasse Made Diabate

There Was a Time (2009)

Best Song: “Sundiata”

Kasse Made Diabate (1949-2018) was a musician from Mali. He was a griot – a member of a hereditary profession responsible for tracking history orally and for recounting (hi)stories through poetry and song. He sang with a group led by his brother Abdoulaye Diabate called Super Mande, and in 1973 they won the Biennale festival (see Orchestre Régional de Kayes section in this same article). He went on to have an incredible career and work with some of the greatest musical artists of his time. The African Classical Music Ensemble was started by Malian musician Tunde Jegede “to celebrate the distinct acoustic classical musical traditions of Africa,” and consists of Jegede himself along with Juldeh Camara and Sona Maya Jobarteh. They’re collaborated with a number of other great artists in addition to Kasse Made Diabate.

From ACME’s website: “There Was A Time is a timeless album that touches on an ancient sound within a contemporary setting. This is completely acoustic Malian music at its very best. The soaring voice of Kassé Mady takes us back to time immemorial where past and present submerge. The lyricism of this album is a living testament to the inherent classicism of this music in its original form. It is a music that creates feelings of joy and melancholy in a single moment. There Was A Time brings us back to the time of our earliest memories.”

I agree – this music is incredible. Any words I could say about it here would be a “nothing burger” – words for the sake of words that really don’t contribute anything. Please just go listen to this album.

My favorite song is Sundiata – it’s the collaborative group’s take on a traditional song named after the great Sundiata Keita – founder of the Mali empire which was ruled about 100 years later by his great-nephew Mansa Musa, who is believed to be the wealthiest person in the history of the world. This song contains the wealthiest flute solo of all time, played on a Malinke style flute (see it in action). Unfortunately, I haven’t been able to figure out exactly who is playing the flute on this recording. Whoever it is deserves a Nobel Peace Prize. Put this song on your biggest, best speaker; turn out every single light in your house; and just lie there on the floor and enjoy this masterpiece. When you open your eyes again you will be living in a world where it really is possible to put the greater good ahead of your own benefit – where it’s possible for peace and friendship to win out over greed – where dreams, really do come true.

That’s it for Good Ovidius’ Top 10 Albums of 2023. I hope you have as much fun listening to these albums this year as I did listening to them last year.

Sincerely,

Lawson

17 January 2024

Downtown Phoenix, AZ