This is my Statement of Purpose I sent in as part of my application to the Liberty University online Ethnomusicology program. I was pretty excited by it when I finished so I thought I'd share.

My name is Lawson Malnory. I am a musician and arts administrator from Dallas (one review also stated I am a notable storyteller). I currently work in the Development Department of the Dallas Symphony in a role that provides valuable opportunities for personal growth as an advocate for the arts. I now intend to engage in post-graduate studies in ethnomusicology to learn the foundation of facts I will need to complement my continued experience with the Symphony in my effort to find my place as an advocate for global unity and understanding through music and culture.

A recent study carried out by researchers from SMU, UCLA, and Belgium, indicated that individuals with higher levels of empathy experience music in a unique way, with more activity in parts of the brain that are involved in feelings of pleasure and in social interaction (Neurophysiological Effects of Trait Empathy in Music Listening - Wallmark, Deblieck, Iacoboni). The latter part of their conclusion is more relevant to my purpose. The researcher from SMU, Dr. Zachary Wallmark, was quoted in one interview saying, “Over and above appreciating music as high art, music is about humans interacting with other humans and trying to understand and communicate with each other.” This idea is profound, but not entirely novel.

In fact, it is thousands of years old.

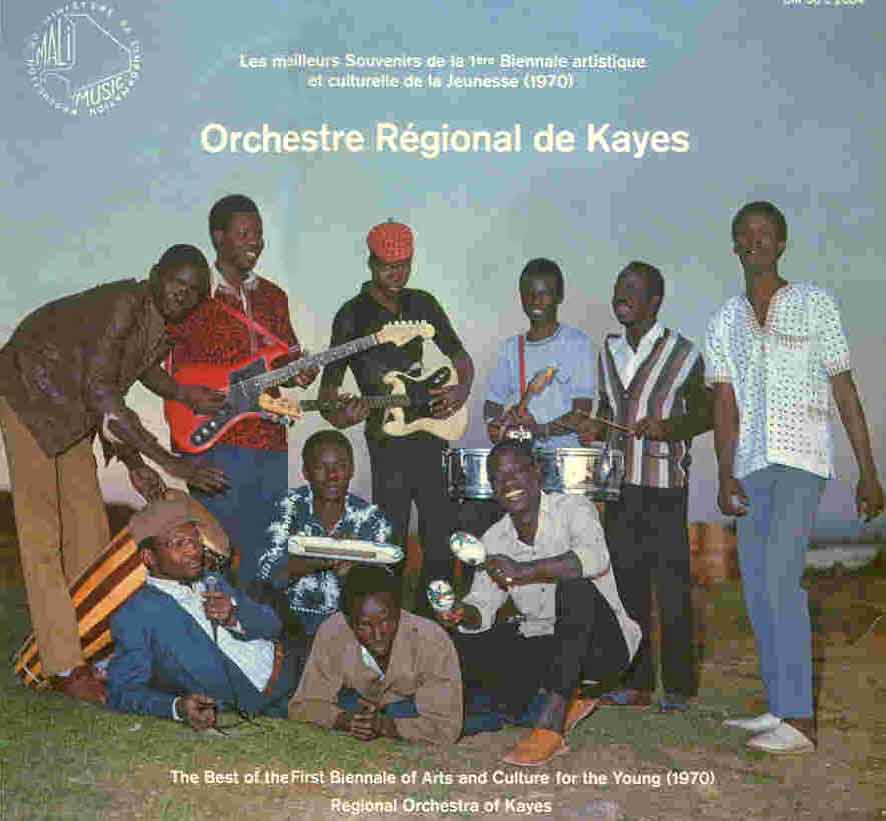

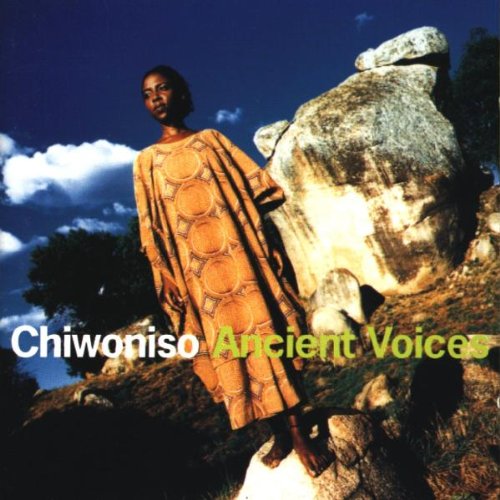

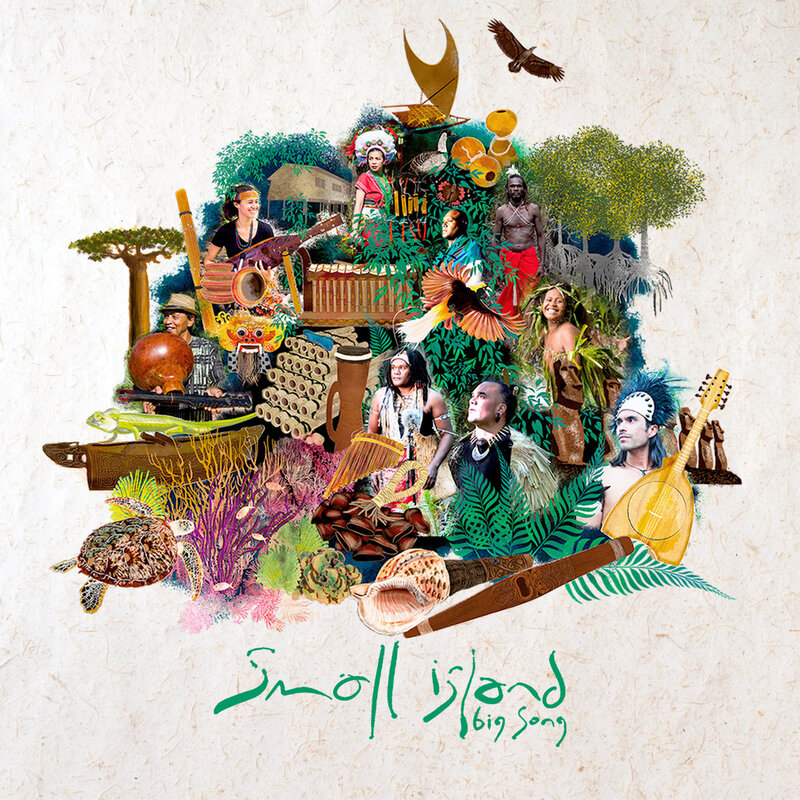

In ancient China, there was an instrument most easily described as split pan-pipes (though pan-pipes is a misnomer, as the instrument bore relatively little significance in Greece and did not originate there). The instrument was a pair of pan-pipes tied together with a length of cord. Each set was played by its own person, and the notes of the scale were split between them such that the players would alternate every-other note to complete the scale. This may seem inefficient by modern standards, but efficiency was not the goal. There was no clear lack-of-technological advancement that prevented the ancient Chinese from creating one set of pipes with a full scale - there must have been a symbolic purpose. Go to Bali and you will hear music built with complex interlocking rhythms between pairs of individuals or groups of musicians. There, they call it kotekan. A similar concept lives in the Shona music of Zimbabwe, where a pair of Mbira players will play the same music, separated by a beat, to create a sound that you can dive into and lose yourself completely as the music continues in a cycle with no clear beginning or end. Why did these cultures develop music that required multiple instruments and performers? Why not simply one-on-a-part as we often have today? Recall what Dr. Wallmark stated in his interview: “music is about humans interacting with other humans and trying to understand and communicate with each other.”

The greatest problems of our time can often be boiled down to a lack of understanding and a lack of communication. From quarrels within married couples to centuries-long conflicts between religious groups, the root is the same. Technology has allowed us to make contact with faraway people and places, but, beyond moderately reliable linguistic computer programs, it does not allow us to understand each other. I believe that music can fill in the gap; that we can learn from the music of ancient cultures that understood its utility for community-building and social growth; that through music, we can come to understand that our differences should bring us together, rather than drive us apart.

Here's the link to the interview with Dr. Wallmark

Meyerson Symphony Center - Dallas, TX - 16 July 2018

My name is Lawson Malnory. I am a musician and arts administrator from Dallas (one review also stated I am a notable storyteller). I currently work in the Development Department of the Dallas Symphony in a role that provides valuable opportunities for personal growth as an advocate for the arts. I now intend to engage in post-graduate studies in ethnomusicology to learn the foundation of facts I will need to complement my continued experience with the Symphony in my effort to find my place as an advocate for global unity and understanding through music and culture.

A recent study carried out by researchers from SMU, UCLA, and Belgium, indicated that individuals with higher levels of empathy experience music in a unique way, with more activity in parts of the brain that are involved in feelings of pleasure and in social interaction (Neurophysiological Effects of Trait Empathy in Music Listening - Wallmark, Deblieck, Iacoboni). The latter part of their conclusion is more relevant to my purpose. The researcher from SMU, Dr. Zachary Wallmark, was quoted in one interview saying, “Over and above appreciating music as high art, music is about humans interacting with other humans and trying to understand and communicate with each other.” This idea is profound, but not entirely novel.

In fact, it is thousands of years old.

In ancient China, there was an instrument most easily described as split pan-pipes (though pan-pipes is a misnomer, as the instrument bore relatively little significance in Greece and did not originate there). The instrument was a pair of pan-pipes tied together with a length of cord. Each set was played by its own person, and the notes of the scale were split between them such that the players would alternate every-other note to complete the scale. This may seem inefficient by modern standards, but efficiency was not the goal. There was no clear lack-of-technological advancement that prevented the ancient Chinese from creating one set of pipes with a full scale - there must have been a symbolic purpose. Go to Bali and you will hear music built with complex interlocking rhythms between pairs of individuals or groups of musicians. There, they call it kotekan. A similar concept lives in the Shona music of Zimbabwe, where a pair of Mbira players will play the same music, separated by a beat, to create a sound that you can dive into and lose yourself completely as the music continues in a cycle with no clear beginning or end. Why did these cultures develop music that required multiple instruments and performers? Why not simply one-on-a-part as we often have today? Recall what Dr. Wallmark stated in his interview: “music is about humans interacting with other humans and trying to understand and communicate with each other.”

The greatest problems of our time can often be boiled down to a lack of understanding and a lack of communication. From quarrels within married couples to centuries-long conflicts between religious groups, the root is the same. Technology has allowed us to make contact with faraway people and places, but, beyond moderately reliable linguistic computer programs, it does not allow us to understand each other. I believe that music can fill in the gap; that we can learn from the music of ancient cultures that understood its utility for community-building and social growth; that through music, we can come to understand that our differences should bring us together, rather than drive us apart.

Here's the link to the interview with Dr. Wallmark

Meyerson Symphony Center - Dallas, TX - 16 July 2018